In Happiness (1998), the ever-smiling Trish (Cynthia Stevenson), in her neat kitchen, is strongly reminiscent of the female ideal as propagated in American films and commercials of the 1950s and 1960s. However, her affected demeanour und put-on optimism cannot hide the illusion behind the image of the idyllic home that is associated with the American Dream of success and prosperity. Trish is a caricature of the perfect housewife and mother, while her younger sister Joy (Jane Adams) represents the eternal adolescent, still seeking a goal in her chaotic life (and with a name that stands in stark contrast to this hypersensitive, sad-looking woman in her late twenties). The pursuit of happiness – one of the three unalienable rights proclaimed in the United States Declaration of Independence – is an empty phrase in Solondz’s films, which repeatedly challenge the notion of happiness.

In both Happiness and Life During Wartime (2009), Solondz explores controversial topics such as sexual obsession, murder and paedophilia. Among the characters of Happiness are a telephone-sex fetishist (Philip Seymour Hoffman), a psychiatrist who turns out to be a paedophile (Dylan Baker), a young woman (Camryn Manheim) who kills and dismembers the doorman of her apartment building after he has attempted to rape her, and a nymphomaniac author (Lara Flynn Boyle). Life During Wartime follows the destinies of several of the characters introduced ten years earlier in Happiness, recasting the returning characters with new actors. There are also links to other films by Solondz, with, for example, Mark Wiener and his father making a brief reappearance in Life During Wartime. This link to Dawn Wiener, the protagonist in Welcome to the Dollhouse (1995), reinforces the strong intertextuality that Solondz builds up, creating his own cinematic universe out of returning characters and the obsessive reappearance of certain topics.

Happiness could instead be called Loneliness, for Solondz’s characters are lonely souls longing for love and acceptance. “We are all alone,” says the psychiatrist Bill to his wife Trish, thereby identifying the problems with communication that the characters have. In both Happiness and Life During Wartime, human tragedy is enacted behind closed doors, and the feeling of closure is heightened by frequent close-ups and interior shots that block the view and at the same time imply psychological imprisonment. This is particularly clear when Bill (Ciarán Hinds) leaves prison in Life During Wartime as a tiny, insignificant human figure framed in front of the dark and tightly closed prison gate.

The lack of communication in these two films is consistent with the characters’ selfishness and isolation, with their narcissism and loneliness. Solondz’s America is a place inhabited by immature people where the dream of eternal youth is reduced to absurdity. This lack of maturity is manifested by the sexual preferences of the protagonists, who are unable to lead a normal sex life. Bill’s reflection in a mirror not only confronts him with his dark and violent side but also evokes the narcissistic image of a man who, in his retarded emotional development, can only find satisfaction in sex with young boys.

After his release from prison, Bill states that he is far from being healed, and Joy (Shirley Henderson), Helen (Ally Sheedy) and Allen (Michael Kenneth Williams) have not changed much either ten years after Happiness. Joy is still the same naïve and neurotic woman, Helen has lost neither her arrogance nor her sexual appetite, and Allen continues to make obscene telephone calls to women. In this second film, he is not played by the fair-haired Philip Seymour Hoffman but by the Afro-American Michael Kenneth Williams. This change clearly indicates that human behaviour does not depend on skin colour, gender or social status. The different cast and the unsettling humour which permeate both films present a challenge to the viewer, forcing them to critically reflect on their own position with regard to the problematic topics that Solondz deals with.

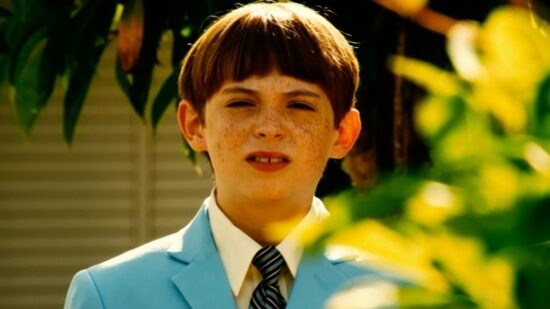

The family as a social microcosm is the filmmaker’s special dramatic space. There is no idyllic family life as in many mainstream films and series, and the notion of the happy family is revealed as a fake, one example being Trish’s dream of the ideal home, which is destroyed when she learns about her paedophile husband’s secret life at the end of Happiness. Life During Wartime addresses directly international terrorism in the aftermath of 9/11 and the Arab-Israeli conflict. However, the most important battles in both Happiness and Life During Wartime are fought inside families and inside human beings. They are symbolized by the generation gap and enacted in conflict situations linked to sexual awakening. “What does it mean to become a man?” asks Timmy (Dylan Riley Snyder) before his bar mitzvah in Life During Wartime. The question could be “What does it mean to be a child or an adolescent in the films of Todd Solondz?”

Solondz uses the topic of paedophilia to explore America’s ugly side and the nation’s ambiguous attitude towards violence, doing so once again through a highly introspective social portrait. In Happiness, the psychiatrist Bill Maplewood is presented as both the caring father and the paedophile who sodomizes his son’s friend after drugging the boy’s dessert. However, Solondz does not depict this child-molester as a monster. In Life During Wartime, Bill’s reflection in the mirror reveals his distorted personality, and he is shown as a most pitiful figure when – scruffy, dirty and almost starving – he begs his elder son Billy (Chris Marquette) for a glass of water. Solondz’s cinema offers no easy clues for identification and he avoids demonization and victimization, instead presenting characters who are riddled with contradictions.

The original title of Life During Wartime was to be Forgiveness, and it is the urge for forgiveness which permeates the film. All the characters ask for forgiveness, but not all are forgiven, including Bill, whose son Billy is unable to forgive him. Billy’s brother Timmy, who believes his mother’s lie that Bill is dead, proudly states: “I am the man of the house.” But on the day of his bar mitzvah he bursts into tears and cries out for his father. At that very moment (and unnoticed by his son), Bill passes by in the background. In these last shots, Bill’s body looks translucent, not unlike a walking ghost. The father figure is the haunting absence-presence in the dysfunctional Maplewood family, a figure both feared and longed for, suggesting that the wounds of childhood never heal.