In 1971, Private Gary Hook (Jack O’Connell), a young British soldier from Derbyshire, arrives in Belfast with his platoon. His unit provides support for the Royal Ulster Constabulary, and while withdrawing after a mission, Gary is accidentally left behind and starts a nightmarish journey through unknown territory.

In one of the first sequences of ’71, an officer gives the soldiers a rough description of Belfast’s topography as a divided city, referring to streets such as the Falls Road and the Shankill Road as important for knowing whether they are in the Catholic or the Protestant sector. However, the absence of street signs on their mission leads to disorientation, and Gary, left alone in a hostile space, tries to find his way in a city which is portrayed as a maze of alleys and courtyards, walls and fences, all creating constant visual closures. The blackened, run-down brick buildings, the uniformity of the architecture, the wrecks of burnt-out buses, burning cars and barricades are part of the iconography familiar from feature films and documentaries about the so-called Troubles. The reduced palette, dominated by grey, brown and greenish colouring during the daylight scenes, heightens the impression of despair and neglect.

Most of the film takes place at night, making the city appear even bleaker and a completely alien and dehumanised place. The nocturnal manhunt evokes Carol Reed’s Odd Man Out (1947), but there is nothing of that film’s romanticism. The protagonist’s journey is a descent into hell; a hell of violence, corruption and political intrigue. Night itself becomes a character in the film. The streets with their rows of houses and narrow alleys are plunged into a yellowish, all-invading light in which the human figure is no more than a dark silhouette, as anonymous as the surrounding space.

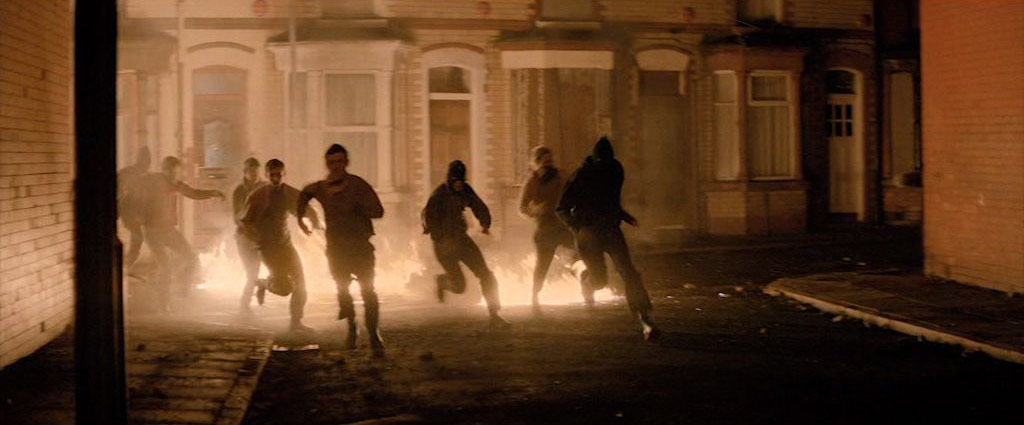

Suddenly, a deserted street is illuminated by a firebomb and young men appear from all sides, running and trying to escape and hide – shadowy creatures of the night. After the explosion in a pub, the light slowly filters through a veil of smoke, reinforcing the protagonist’s feelings of fear and confusion. The blurred image and the absence of sound recreate the situation as the young soldier experiences it, briefly becoming deaf and dizzy. The impenetrability of the night also contributes to the atmosphere of danger and loss and is supported by the framing and camera positions.

The extreme fragmentation caused by fast camera movements and dynamic editing and the torrential rain at the end of Gary’s nocturnal escape further underline chaos and violence. Realism is transcended by stylisation, with the streets of Belfast transformed into a metaphorical space. The frequent use of lingering Steadicam shots makes the chaotic events and the protagonist’s inner confusion even more tangible.

One long sequence takes place in the Divis Flats, a place the officer had warned the newly arrived soldiers of as a “very dangerous” IRA stronghold. Located at the frontline between the Falls Road and the Shankill Road, this huge complex of tall buildings is a labyrinth of seemingly endless passages, corridors and staircases in which Gary finds himself trapped. Harsh artificial lighting contrasts sharply with dark corners, suggesting that danger lurks everywhere. The atmosphere of gloom is suspended just once, when Gary enters one of the flats, where he is watched by a little girl. The red hair of the child, her light blue sweater and the similarly light blue wallpaper suggest an oasis of peace, but this lasts only for a few seconds.

Gary has other more dramatic encounters during his desperate escape in hellish Belfast, encounters of hatred but also of friendliness, and all of them visibly affect him. A Protestant youngster seeking to avenge his father’s death at the hands of the IRA talks incessantly of “Bloody Fenians” and is intent on proving his manliness. The explosion in the pub blows off his arms, leaving him looking like a ragged doll. Eamon, a former paramedic and unaware that Gary is a soldier, takes him to his home in the Divis Flats complex and treats his wounds.

Jimmy Quinn and another IRA man are on Gary’s tracks, determined to kill him. The MRF (Military Reaction Force) have him on their hit list too because he has seen one of their number in the pub near the Shankill Road and therefore knows that the MRF provided the Protestant paramilitaries with the explosive for the bomb. Later, an MRF man tries to strangle Gary to prevent him testifying to how the state is inciting the violence.

Gary, who is not sure whether he is Protestant or Catholic, is more the witness and target of violence than its perpetrator. When riots start in one of the streets, he remains passive, the helpless observer of the brutality of RUC agents and of the death of a fellow soldier in his unit. Close-ups of his face reveal his growing awareness of a reality he couldn’t have imagined before. He becomes the victim of a manhunt but has the strength and training to survive the night. At the same time, however, he remains human.

He kneels next to the IRA man he has stabbed in the stomach as if he wants to help him die more peacefully. At this point, as in many other situations in the film, there is no dialogue. Its absence and the eerie soundtrack, sometimes very low-key, contribute to the vivid portrayal of a violent world, and reveal the protagonist’s journey into night as an inner struggle.

Night is the appropriate setting for violence and political intrigue. The conflict is not simply between Catholics and Protestants but also between different factions within the IRA, represented for example by the rivalry between Boyle and Quinn. The MRF not only provide the Protestant paramilitary groups with explosives but they also do deals with the IRA, trying to keep the rivalries alive and gain new allies among the Catholic paramilitary groups. Confusion is a term which is frequently used in the film, and the imagery of confusion and chaos points to the complex entanglement of official policy and terrorism in which the ordinary soldier Gary is caught. At the end, confusion reigns and truth is concealed.

The final sequence shows the protagonist and his younger brother Darren on a bus. Gary is now wearing civilian clothes and his adolescent brother is asleep, his head on Gary’s lap. The bus disappears into the Derbyshire countryside under a sky tinged with blue and pink. An image too beautiful to be true? Before these final shots, Gary is shown at the home where Darren has been staying during his absence. When nobody opens the door, he starts shouting and beats the door with his fists, then vents his aggression verbally on the warden.

His dramatic initiation during that night in Belfast has made a man of him, someone who insists on his rights vociferously and is no longer the mere cannon fodder of the system. Has the terrifying experience made him a better person? The film shies away from answering this question. However, the final shot in the Derbyshire countryside suggests an illusion and thus casts doubt on the notion that the individual has any power within a system that sacrifices not only its young men but truth as well.