Three Resurrected Drunkards (Kaette kita yopparai, 1968) starts with a long sequence showing three young men enjoying themselves on a deserted sandy beach one sunny day. Their haircuts and clothes indicate that they belong to the beat generation, and their beige jackets are reminiscent of those worn by The Beatles for their concert at Shea Stadium in New York in 1965. While the song “Kaette kita yopparai” (“a drunkard who came back”) is heard in the background, the three young adults mimic a shooting scene, using a hand and fingers to represent a gun and pointing it at the head of one of them. The protagonists are played by the members of the Japanese folk and pop group The Folk Crusaders: Kazuhiko Kato, Osamu Kitayama and Norihiko Hashida. The film’s Japanese title is that of their eponymous song about a man who has died and goes to heaven – described as a place of leisure where women and alcohol are available – but is suddenly scolded by God, who says: “Heaven isn’t such an easy-going place.” These words are thundered by a voice from offscreen while an aeroplane can be seen in a general shot of the sky.

This image reveals a reality that is very different from the young men’s carefree attitude and the peaceful setting of the beautiful beach and the open sea. Very soon after, they are forced to face this different reality. While they are swimming in the sea, a mysterious hand reaches up from under the sand and steals the clothes of two of them, replacing their fashionable attire with a South Korean military uniform and a Korean student’s uniform. Instead of copying western models, the three protagonists are now given the identities of refugee army deserters and illegal immigrants. Mistaken for stowaways from Korea, they have to hide from the police and also from the two Koreans to whom the uniforms belong and who are eager to kill the three Japanese in order to lead the identity switch to its logical conclusion.

Clothes become an identity signifier, challenging the real identity of the two Japanese in the uniforms and their friend, who stays with them as a cover-up. The three young men are confronted by anti-Korean sentiments and behaviour. Oshima had already addressed this topic in Death by Hanging (Koshike, Japan, 1968), but in Three Resurrected Drunkards, he approaches it in a somewhat surreal manner, already presaged early in the film by the disembodied hand in the beach scene. Mixing dream and reality, he presents serious social criticism through comical exaggeration.

The three young Japanese are taken for mikkosha or stowaways – in many cases Koreans who were illegal immigrants. The film’s use of the term Chosen to refer to Korea, evoking the name of the country when it was a Japanese colony (1910-1945) reveals a discriminating attitude towards Koreans that underlines their still inferior status in Japanese society. Koreans were exploited as cheap labour during the Japanese annexation. After 1946, tens of thousands of immigrants whose names do not appear in any official document have come from Korea to Japan. Oshima alludes to the absence in official records of these illegal immigrants, and the consequence of their “invisibility”: a life in poverty and fear at the margins of society. Unlike the three protagonists, who are representatives of the Japanese middle class, these Koreans did not benefit from Japan’s post-war economic boom.

The young men almost manage to get rid of the uniforms but are quickly forced by the two refugees from Korea to put them on and play the role of Koreans again. This change of clothes – something that is repeated several times in the film – is a reference to shifting identity and reflects the alien status of many Koreans of the second or third generation in Japan, who were Japanese in terms of culture and language but, because of their ethnic background, had to face (and still today face) social and economic discrimination.

One of the stereotypes about Koreans for Japanese people is an inclination to resort to violence, and in the film the two Koreans have a pistol that they do not hesitate to make use of. However, and in keeping with the satirical approach, violence has a strong playful element and the scenes are highly stylized. Moreover, the two men, and also the mysterious Korean woman who at one point helps the Japanese young men escape with their lives, show a great deal of pride, and this challenges the feeling of superiority that the Japanese had in the uneasy Japanese-Korean relationship throughout the 20th century. At the end of the first part of the film, the three protagonists are interviewing people in a crowded street, asking them if they are Japanese. The standard answer, which is “no,” defies the nationalist concept of Japanese ethnic homogeneity.

The topic of anti-Korean racism is set in the broader context of the Vietnam War. The Korean soldier has fled from his country to escape military service in Vietnam. Oshima also refers to the American military presence in Japan by showing a roadside sign that indicates a nearby American military base. In a dream sequence, the three protagonists are sent to Busan, and from there to the battlefields in Vietnam, where they are killed. Woken up by the mysterious Korean woman, they find themselves still alive and in Japan.

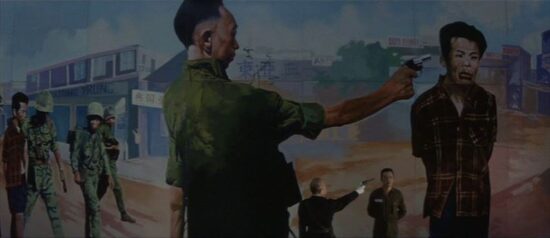

Death and violence permeate the film. The mimicking of a shooting is a motif that recurs, with variations, in a number of sequences and with a real firearm when the Korean soldier is the person to be shot. What at first looks like a silly game but gradually becomes more violent has its origins in brutal reality. A wall painting showing the famous photograph by Eddie Adams that later won the Pulitzer Prize figures prominently in a series of shots in the final sequence. It shows a Vietcong prisoner being executed by the chief of the South Vietnamese national police in the streets of Saigon. The photograph was taken on 1st February 1968, and Oshima’s film was released only a few weeks later, on 30th March, underlining his strongly-felt concern about the political situation of his time.

The three protagonists are first presented as rather carefree young men, eager to enjoy life after graduating from university. What they experience, although it appears strange, seems to mark the end of their youth. However, their death on the battlefield in Vietnam is only a dream. Oshima gives them a second chance, and their “resurrection” is made possible by the medium of film. Thus, after the interview sequence, the action returns to the sequence on the beach at the beginning. The young men are now able to anticipate the situations they have to face after the discovery that their clothes have vanished, and the storyline takes a different turn.

The attitude of the protagonists slowly changes from carefree behaviour to a feeling of responsibility, and when they assume Korean identities, the chain of violence in which they were caught is broken. However, there is no happy ending as in the American comedy Groundhog Day (1993), produced many years later with a similar story of different behaviour when the protagonist relives a situation. The young men are now the helpless witnesses of the execution of the two Koreans by a Japanese police officer who adopts the same pose as the South Vietnamese police chief when he shoots the two men in front of the painting of Eddie Adams’s famous photograph. The Koreans thus remain victims in Japan, a country still haunted by its colonial past and the atrocities of World War II that cost the lives of many Koreans. However, Japan is now siding with American imperialism.