Of the three films comprising Gus Van Sant’s so-called “Death Trilogy” (the others being 2002’s Gerry and 2005’s Last Days), Elephant (2003) remains the most affecting and prescient. Although a major success at Cannes, earning both the Palme d’Or and Best Director awards of that year, it is largely overlooked in comparison with the rest of the writer-director’s eclectic body of work.

The film’s relative obscurity may be due in part to its formal experimentation (it mostly consists of extended, often wordless tracking shots that follow characters from behind) or disturbing subject matter (a school shooting in Portland, Oregon). Perhaps it has something to do with Van Sant’s choice to cast mostly non-actors, many of whom have not appeared in anything before or since its release.

Despite its sensitive material, it is a marvel on a purely technical level. The late, great Harris Savides served as its director of photography, and the aforementioned tracking shots, coupled with Leslie Shatz’s otherworldly sound design (which incorporates, among other things, distorted text readings by William S. Burroughs), are breathtaking.

One mesmerizing sequence follows John (John Robinson) as he plays with a classmate’s dog; after John calls out to the animal, Van Sant uses slow motion to track the dog’s contortions as it jumps up to the boy’s upraised hand. It is a moment of simple, but striking imagery, its significance underlined by the fact that in the very same shot one can see the armed shooters approaching the school. The fleeting happiness with the dog will very soon be shattered by horrific violence.

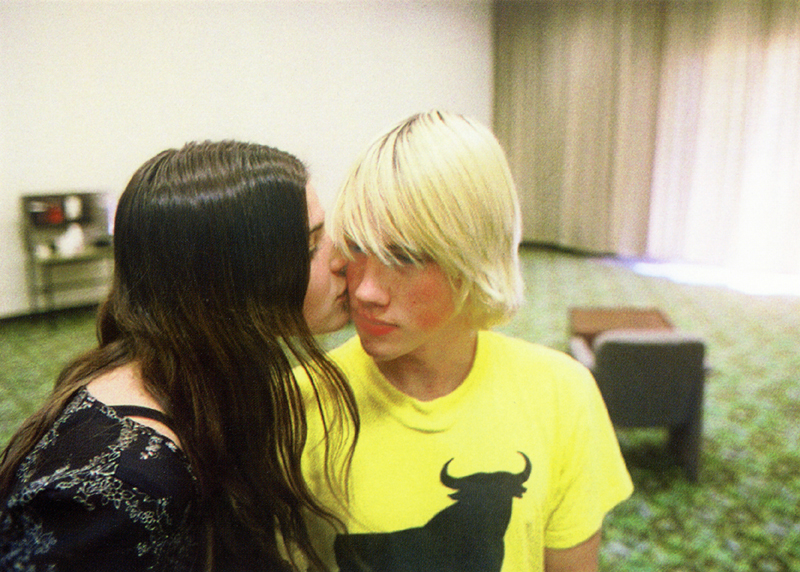

Wisely, Van Sant mostly foregoes such stylistic flourishes when portraying the killers, Alex (Alex Frost) and Eric (Eric Deulen). The shooting itself, though gut-wrenching, is only a few minutes long. The deaths are sometimes shown on screen, but they are not dwelled upon and are often out of focus. This matter-of-fact approach to violence allows Van Sant to mostly avoid exploitation.

Despite such precise methods, the film is not perfect. One shot, a POV looking down the barrel of one of the killers’ guns, feels terribly out of place. The parallel to first-person shooter games is obvious: it echoes a previous scene in which Eric plays a similar game on his computer. It is a startling moment, especially because it forces the viewer to stand in the killer’s shoes, and is discordant with the rest of the film’s objective aesthetic.

As a teacher, I find Elephant particularly difficult to watch, let alone write about. Nevertheless, it is among Van Sant’s most important works, precisely because of its difficulty. Many complain that it is boring, monotonous – and in some ways, they are correct. But this banality is part of what makes the film so deeply upsetting. These kids look and act like those living in any given Middle-American neighborhood; their school could be the one right down the street.