She rips the sleeve off of a denim shirt and makes herself two bandanas to wear around her neck. She’s dressed in washed-up blue jeans, white cowboy boots and white tank top. She then sits next to an old man with a beat-up white cowboy hat on. She takes off all her jewellery, her earrings, her rings, and watch, and gives it to him. A little later on, we see her with the hat. “Where did you get the hat?” asks Thelma. “I stole it,” Louise replies. She had in fact traded all the possessions she had left, except for the car, for the hat.

Why the cowboy hat? Is it because the cowboy embodies the idea of a great adventure? Is it because it embodies a well defined character? Is it because he doesn’t dwell on the past because his kind of life only allows him to live in the present? Is it because his lifestyle, just as the road adventurer, just as the outlaw, alone on the road or in the vast Wild West, is reduced to the essentials of survival, stripped of possessions and committed to an elemental way of dressing, solely out of necessity, making the best of something and someone, himself, with limited resources? Whatever it is, the cowboy hat is the final piece that Louise chooses to define her look. Throughout the film, we see her and Thelma gradually contest and lose the adornments, and trappings we could say, of what is traditionally considered feminine, redefine it and form their own identities, making boyish silhouettes and emblems of the road and of the western their own, a new kind of femininity.

Thelma and Louise (1991), directed by Ridley Scott and scripted by Callie Khouri, bends so many genres, having been predominantly acclaimed as female revenge movie or female liberation and empowerment film, but to not see it as what it first and foremost is, a groundbreaking road movie, would mean to reduce it to a sub-genre of feminist cinema meant to please academic film criticism, which would be an injustice. Moreover, this is a road movie in outlaw and buddy movie trappings, standing alongside another great of the kind, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. But by making both protagonists female, Thelma and Louise formed its own identity. Another pivotal element, more important than any feminist appeal, was that the film, just like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, depicted real bonding and real friendship of two memorable characters. Because despite common belief, that doesn’t come off that easily, neither in real life nor in film. In life, it’s rare to find people to take a journey with, let alone a life and self-defining journey. In film, it has rarely been depicted truthfully. Maybe that’s why the film has appealed so much to both men and women. Because every great film does not consider gender.

They took to the road to escape their tedious lives, and then the law, and while on the road they are finally happy and free, freed from their past and from all the restraints that held them back. It is a journey, they cannot remain the same. Their clothes – Elizabeth McBride was the costume designer – cannot remain the same either. They lose or leave behind everything and everyone, and they trade or let go of many of their clothes, too. What is interesting to see is how denim, present from the very start in both Thelma and Louise’s wardrobes, this symbol of American fashion sensibility and universal modernity, function-grounding and gender-breaking, and which should stand for unapologetic American coolness, has its own arc in the film. Like the ugly truth and limitations that lie underneath the great American Dream and the promise of freedom, a piercing commentary is made throughout the film by Ridley Scott by contrasting the American great outdoors (with all the patina, texture and hardness of light that is the stuff of myth and legend) with the run-down dwellings, crummy interiors and small-town harsh reality. All denim is not the same.

They took to the road to escape their tedious lives, and then the law, and while on the road they are finally happy and free, freed from their past and from all the restraints that held them back. It is a journey, they cannot remain the same. Their clothes – Elizabeth McBride was the costume designer – cannot remain the same either. They lose or leave behind everything and everyone, and they trade or let go of many of their clothes, too. What is interesting to see is how denim, present from the very start in both Thelma and Louise’s wardrobes, this symbol of American fashion sensibility and universal modernity, function-grounding and gender-breaking, and which should stand for unapologetic American coolness, has its own arc in the film. Like the ugly truth and limitations that lie underneath the great American Dream and the promise of freedom, a piercing commentary is made throughout the film by Ridley Scott by contrasting the American great outdoors (with all the patina, texture and hardness of light that is the stuff of myth and legend) with the run-down dwellings, crummy interiors and small-town harsh reality. All denim is not the same.

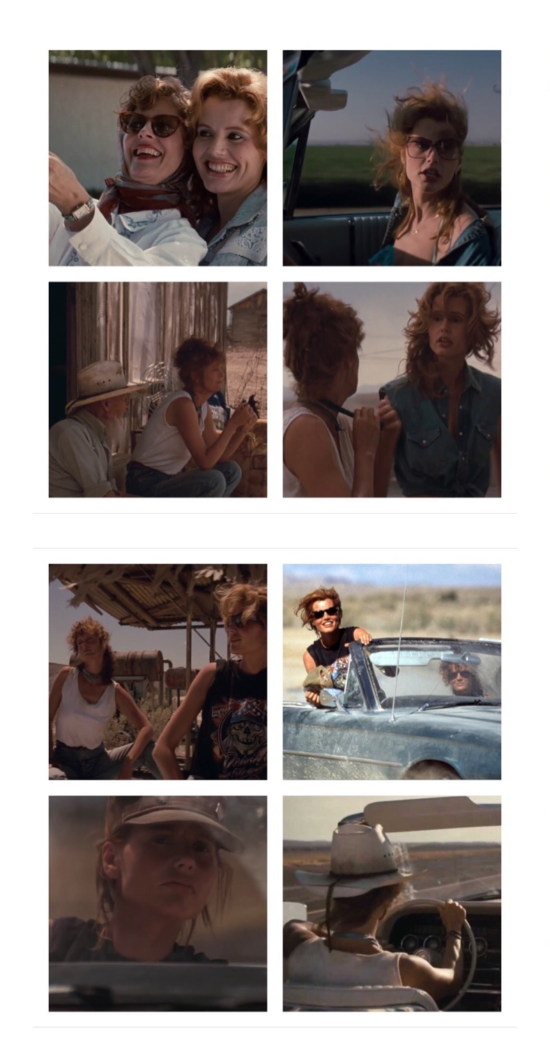

Louise, the older and wiser and more bitter of the two, is wearing her faded jeans, hardware leather belt and white cowboy boots when they hit the road, and pairs them with a white shirt. But it is not the kind that may be borrowed from the boys. It is embroidered on the collar, and Louise is wearing ladylike cat-eye sunglasses and a colourful feminine scarf wrapped around her head to keep her hair neat. Make-up is in place, too. Thelma, younger, reckless and more naïve, is wearing much more conventional feminine clothes, from her floral robe when she’s at home, to a long denim skirt, frilly white top and embroidered denim jacket, and oversized tinted shades. She is also wearing heavy make-up.

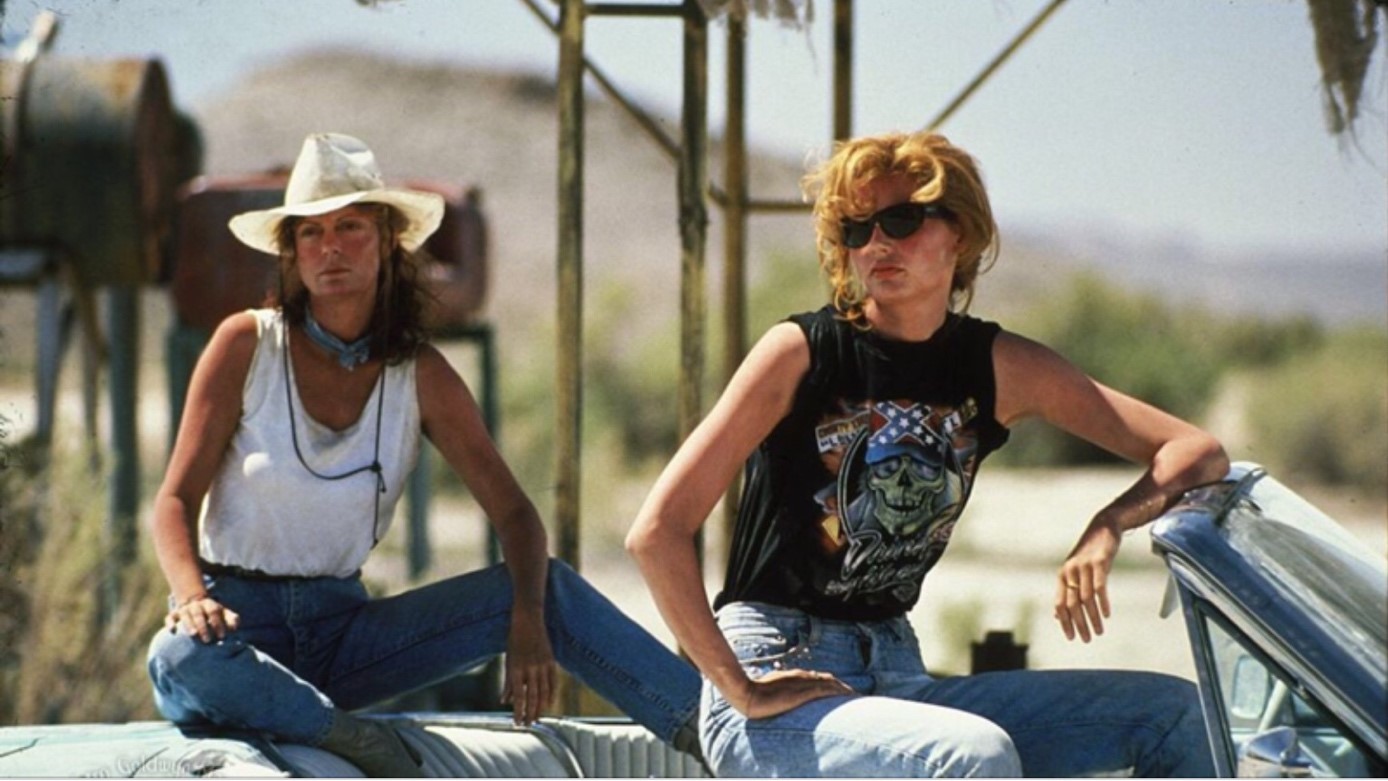

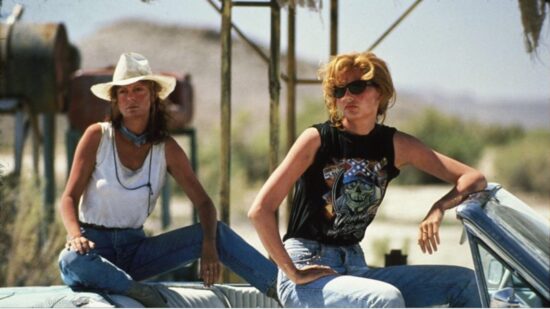

As the story advances, their looks change. Taken out of societal norms, they are shown as individuals. Louise swaps her embroidered shirt for a plain white tank top, her headscarf for two denim bandanas, her jewellery for the old cowboy hat, and her cat-eye sunglasses for a policeman’s aviators. She also adds a hand-band made of some kind of patterned cloth. Thelma goes from her girly clothes to jeans and a sleeveless denim shirt, from her oversized sunglasses to timeless black Ray Ban wayfarers, leaves all her jewellery behind, including her wedding band, drop earrings and necklaces (she only keeps two simple golden bracelets) and ties her tousled braided hair with a denim strap (which probably came from the same ripped-off denim shirt as Louise’s bandanas). Finally, she adds a black graphic rock ‘n’ roll tank top with the line “Driving My Life Away” written on it and the weathered baseball cap she takes from the truck driver during the car spin around him after they have blown up his truck. Thelma and Louise both give up wearing make-up.

With their disheveled and dusty looks, weather-beaten tans, high waist faded jeans, white and black tank tops, their t-shirts becoming symbols of rediscovered sisterhood, cowboy boots, unisex sunglasses and men’s cap and hat, they “become more and more natural, but more and more beautiful as it goes on and by the end… just these mythical looking creatures,” as director Ridley Scott described them. Without make-up, colour, fashion and “things,” exposed to the natural elements, the dirt, the sun fade, the open road, the Grand Canyon, they are illuminated, and their jeans have gained even more character not through years of wear (as it happens with our most beloved pairs of jeans), but through a life-defining journey of wear.

This piece is published courtesy of classiq.me

All film stills courtesy of Pathé Entertainment, Metro Goldwyn Mayer