The Algerian War of Independence was one of the defining conflicts of the twentieth century: a potent symbol of the collapse of European colonialism and the emergence of national self- determination and political agency on the part of previously subjected indigenous populations. The war provoked a UN resolution in support of Algerian independence, an international movement against colonial oppression, and the eventual collapse of the French Fourth Republic. It also inspired Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers, released only five years after the end of the war, and winner of the Golden Lion at the 1966 Venice Film Festival.

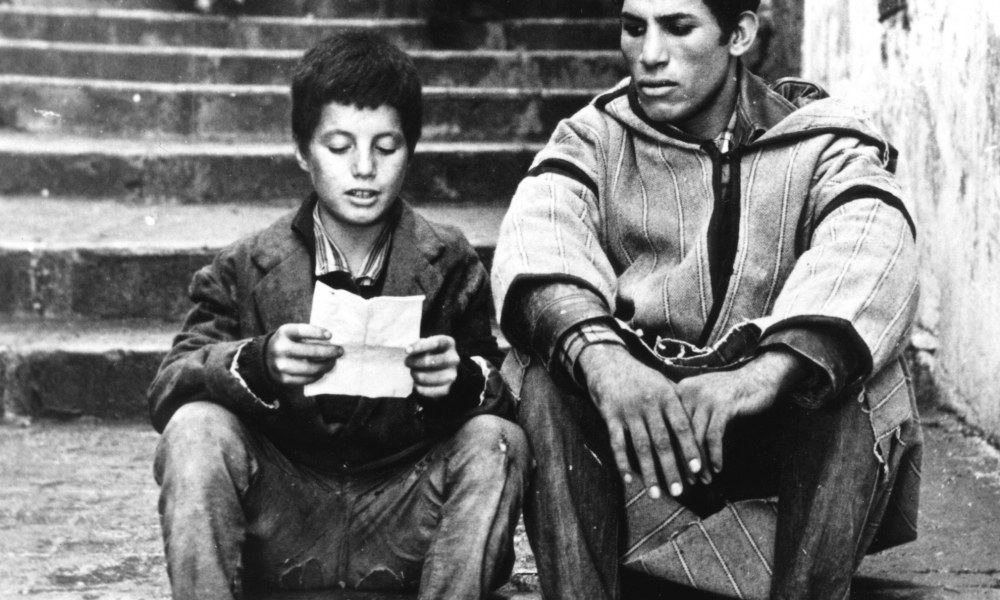

Based on former Algerian Front de Libération Nationale leader Saâdi Yacef’s memoir, Souvenirs de la Bataille d’Alger, the film vividly recreates the sustained violence of a conflict characterised by military brutality, retaliatory acts of terror, war crimes and civilian deaths. The opening scene shows the submission of a victim of torture; an Arab, forced by French soldiers to reveal the hiding place of the last free leader of the Algerian FLN, Ali la Pointe. Pontecorvo then rewinds to document la Pointe’s journey from street hustler to de facto leader of the FLN and, eventually, its martyr.

Through its visceral depiction of violence on both sides, the film bears witness to the bloodshed and loss of life that is the inevitable consequence of intractably opposed political ideologies. The film also stands as an important cinematic analysis of guerrilla warfare and its capacity to succeed against militarily superior forces in the face of seemingly overwhelming odds.

It is said that Pontecorvo decided to become a director after watching Roberto Rossellini’s Paisà, and it’s certainly true that the striking documentary-style realism of The Battle of Algiers, the grainy, high contrast quality of cinematographer Marcello Gatti’s photography, as well as Pontecorvo’s use of amateur actors and hand-held filming techniques reveal the film, and its director, to be children of Rossellini and Italian neorealism. However, part of the greatness of the film lies in the director’s ability to supplement this understated naturalism with moments of genuine Hitchcockian suspense: a drawn out sequence of events leading up to FLN bombings of pied noir civilians is a masterful demonstration of how tension can be built through visual exposition and pacing.

Remarkably, since it is not only based on Yacef’s memoir, but was also partly produced by and starred the former FLN leader, the film is careful to preserve a detached impartiality in describing events. Pontecorvo is content to show the atrocities committed by both sides, allowing the audience to judge the protagonists by the consequences of their actions. Yet this lightness of touch does not undermine the film’s sense of moral conviction: rather, the director is confident that the events depicted speak for themselves. It is impossible for the viewer to watch the overbearing officiousness of the French military presence, the imposition of checkpoints, the ghettoisation of the Casbah and the adoption of murder as a military tactic, without drawing a comparison between French activities in Algiers and the Nazi occupation of France. In the end, the French claim to moral legitimacy with regard to its policy in Algeria is undone by the fact of its own recent subjection to – and liberation from – German imperial ambition. In light of the events depicted, the FLN resembles the French resistance, which is, perhaps, what Pontecorvo and Yacef intended.

The dual format re-release of The Battle of Algiers by new label Cult Films contains a 4K restoration of the film by Italian laboratory L’Immagine Ritrovata and an excellent suite of extras, including interviews with Pontecorvo and Yacef, and a fascinating documentary on the restoration process. The package does justice to Pontecorvo’s film, underlining its status as a masterpiece of political filmmaking and the definitive cinematic document of a conflict that resonates with significance over half a century later.