It seems any film set in ‘outer space’ will have the daunting honour of being compared, almost always unfavourably, to 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Hailed as the greatest achievement in cinematic history, Kubrick’s cold, grand masterpiece has been keeping audiences mystified since its release 46 years ago and banished all subsequent cinematic offerings to potentially rest in its long shadow. This hasn’t deterred directors though: the bar has been set, and 2001-inspired greats in their own right have followed.

The past two years alone have produced two very admirable additions to the genre. Gravity (2013), with its sparse plot and woozy visuals was a complete success in creating what Kubrick refers to as “a non-verbal experience (that) attempts to communicate more to the subconscious and to the feelings than it does to the intellect.” For Gravity’s Ryan (Sandra Bullock), space is a nothingness from which she recreates herself, and her landing on Earth sees her learning to walk again like a newborn.

Second in line is Christopher Nolan’s flashy Interstellar (2014), a visually impressive eco-sci-fi drama. Where Kubrick’s piece of cinema presents images for the audience to interpret as they wish, Interstellar invites a more intellectual approach, and any metaphysical flourishes are dropped in favour of basic human priorities – survival and family. Despite these major thematic differences, nods to 2001 come thick and fast, from composer Hans Zimmer’s Straussian organ-crescendo score, to the film’s impressively psychedelic, time-bending conclusion.

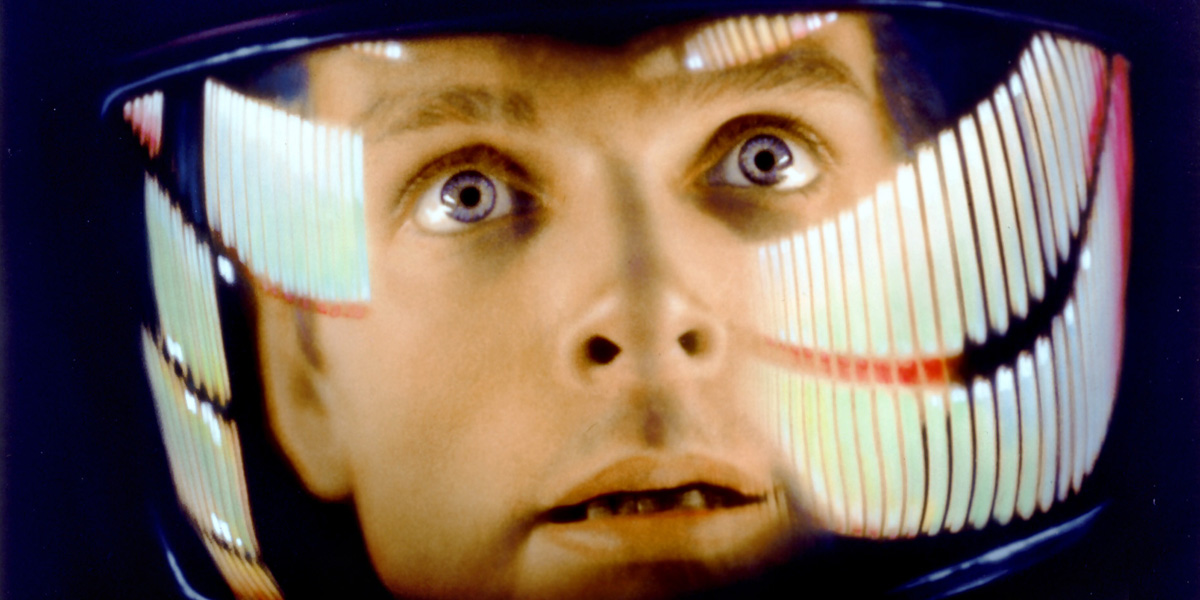

The one moment of solidarity that runs through all of these films is when the protagonist’s tether snaps and they separate from the mothership – an iconic moment in each film that lends itself to a symbolic representation of one thing above all others. In 2001, Dave (Keir Dullea) drifts off into ‘deep space’ and is reborn as the iconic star child. Despite the warm and fuzzy (and definitely un-Kubrickian) emotional core, Interstellar is sure to evoke that same horror when Cooper (Matthew McConaughey) severs his connection from the ship and drifts into a black hole. Similarly, Gravity’s moment of terror comes when Ryan loses her grip and spins off into space. During these moments, all three directors choose to fix the camera on the respective protagonist’s stricken faces, while the score is reduced to breathing and ‘space noise’: hums, screeches and echoes.

Few horror films are enhanced by monsters. The reveal is more often than not a disappointment because nothing is ever as scary or personal as individual imagination, and Kubrick knew this. Giving fear a face in the form of a monster (or alien) is to make it palpable, but there is nothing quite so awe-inspiring – and terrifying – as seeing your explorer severed from the mothership, cocooned in their spacesuit, staring wide-eyed into the ultimate terror: the unknown.