The films of Ernst Lubitsch have become synonymous with bright, colourful characters and situations; accordingly, this is reflected in their various posters and promotional material from the time. Most of these posters – the comedies and romances especially – look to feature Lubistch’s central couple, often in some dramatic and red-cheeked pose, backed by festive imagery. Going on this alone, one might be forgiven for assuming that every Lubitsch film is akin to some kind of raucous, upper class party where the wine flows freely and the night is never old. Of course, that there is much, much more to the man’s oeuvre than crisp dinner jackets and mischievous innuendo. His approach to social satire is second to none, with sex and money as recurring themes that allow for such concise commentary.

Looking first at the standout feature of his 1930s work, Trouble in Paradise (1932), one poster that perfectly captures the spirit of the film is this piece by Swedish artist Gösta Åberg. While a painter by trade, Åberg also made sculptures, as reflected in the statuesque poses of Miriam Hopkins and Herbert Marshall, seen here quietly considering the tempting apple, as a reference to the film’s title. The piece is consistent with much of the Swedish poster art of the period, with bold primary colours and the occasional three-dimensional typeface.

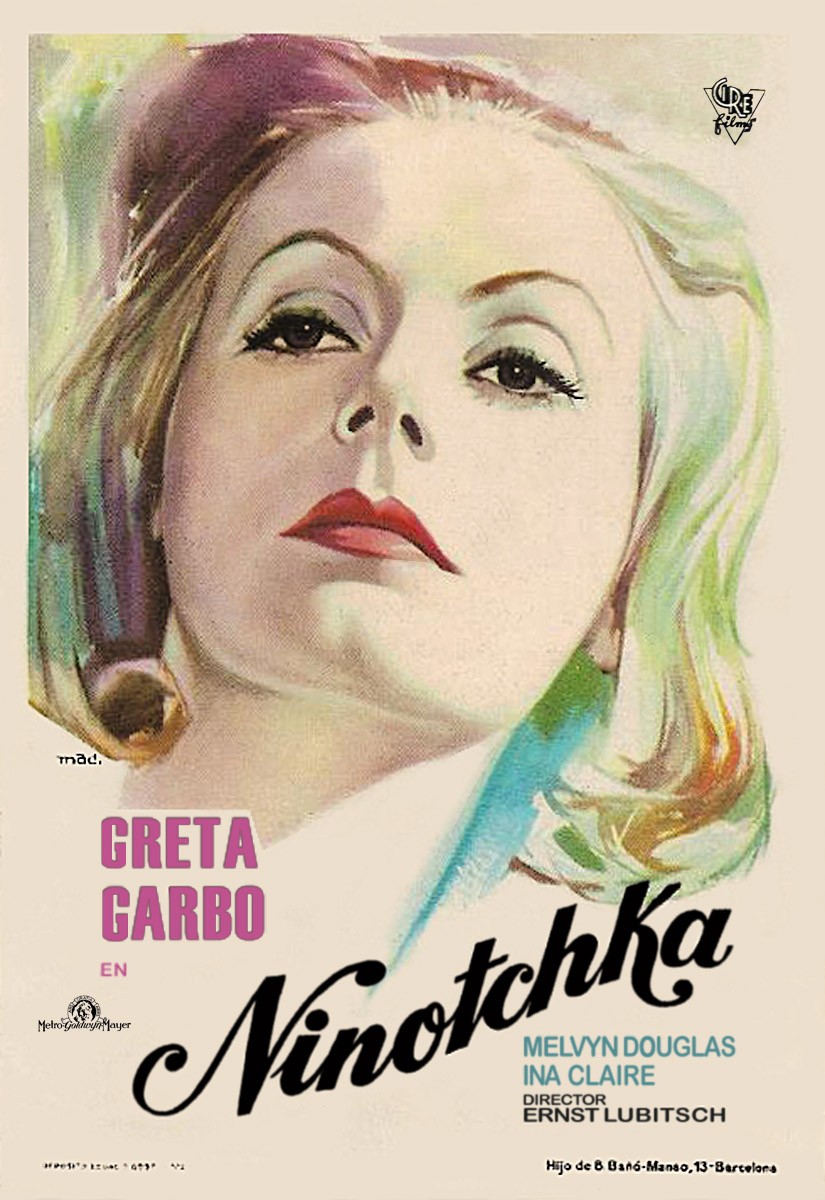

This is in stark contrast with the poster fashioned for the Spanish release of Ninotchka (1939) by Macario Gómez Quibus. Here, the artist (who typically signed his work under the name Mac) instead looks to capture the strong lines of Greta Garbo’s face in all its Scandinavian beauty.

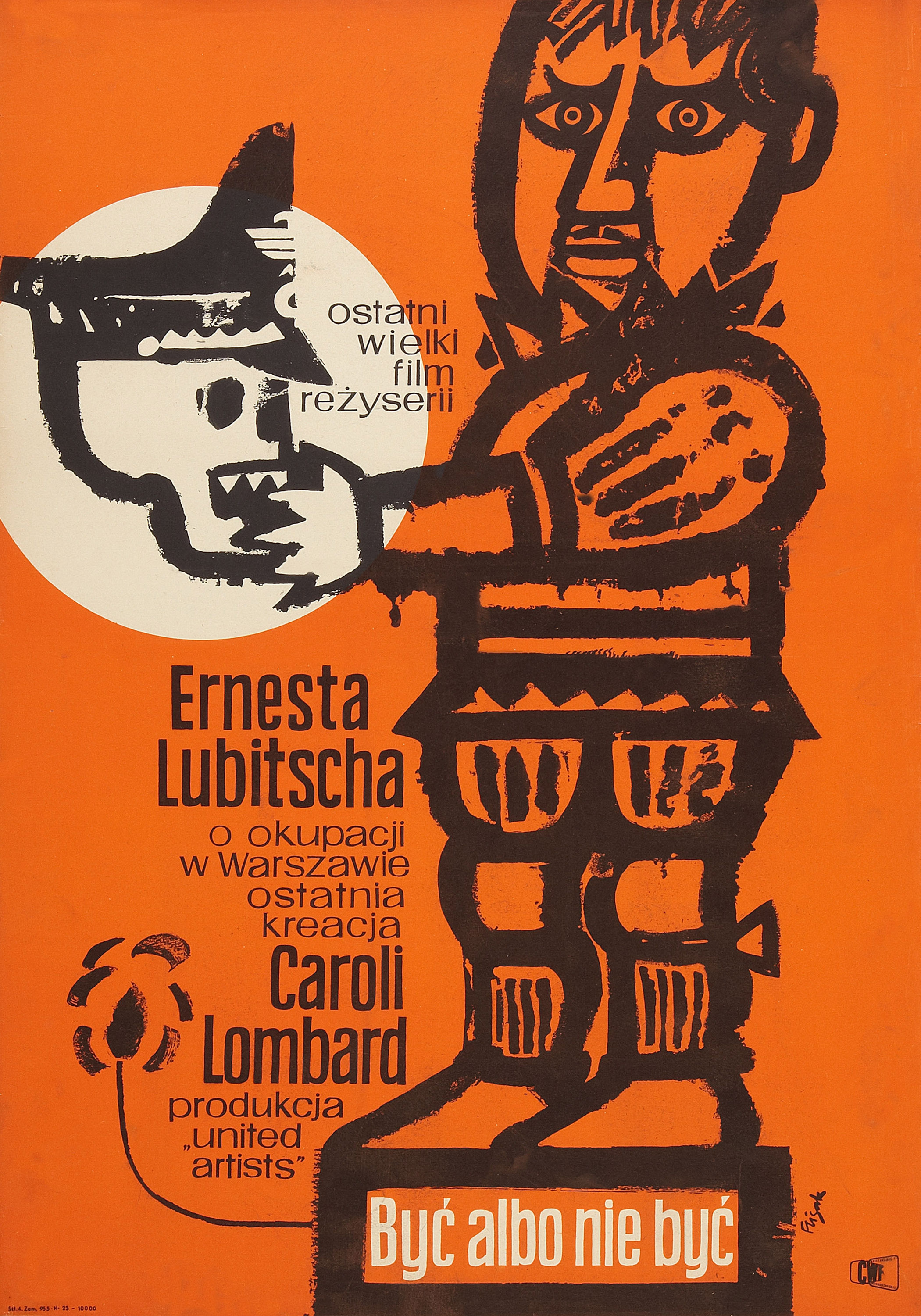

Thirdly, and in a violent departure from the classic film poster form, two bold, modernist examples provided by Poland’s Jerzy Flisak and Germany’s Hans Hillman respectively for Lubitsch’s To Be or Not to Be (1942). We all know by now of the great legacy that is Polish poster design; Flisak was one of the most prolific of the period, beginning life as a satirical cartoonist which would explain the thick brush strokes and sparse use of colour here.

Hillman on the other hand was one of Germany’s most important graphic artists, with a strong emphasis on the minimalist – often reducing a film’s premise to a mere handful of shapes.

Finally, a more traditional and painterly example created by the Roman artist Anselmo Ballester for Heaven Can Wait in 1943.