The technology of film can been considered a time machine of sorts. It can transport the audience from one particular time period to another, allowing them to bask in the glory of the neologistic innovations of the time. Let’s take a trip to a time when filmic and musical recording equipment such as the videocassette tape was the zenith of technological sophistication: the 1970s. Brian De Palma’s 1974 cult musical horror Phantom of the Paradise suffuses an array of audio-visual technologies with horrific and unsettling imagery. The result is an astute social commentary on the vagaries of the music industry and the over-saturation and over-reliance on technology.

The technology, although incredibly dated now, was top of the range forty years ago. It is in this sense that we are transported back to the 1970s when watching the film, not only in terms of mise-en-scène (‘70s clothing, hair styles, etc.), but also in terms of the cultural unease surrounding ever-growing technological sophistication and distribution. The elements of music, horror, and technology are conflated to create a distressing tale of corruption and inauthenticity in the music industry and the technologies that sustain it. De Palma’s film serves as an eerily prescient review of today’s music industry and the ubiquity of ever-developing technologies.

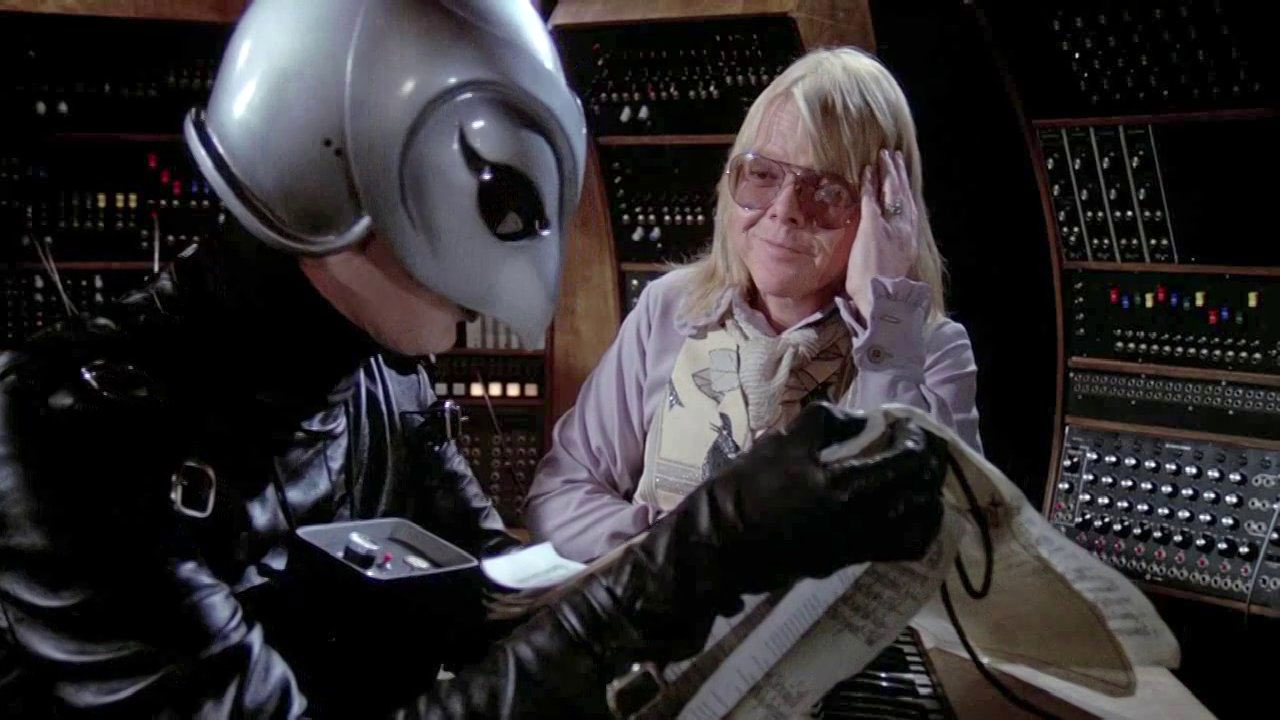

The story involves a duplicitous record producer named Swan and his intentions to open a rock ‘n’ roll extravaganza called The Paradise. To do so, he steals the music of the talented and ambitious Winslow Leach and has him wrongfully incriminated in the process. Leach, driven mad by the thought of his music being exploited in order to further Swan’s corporate capitalist agenda, escapes and haunts over the Paradise as the Phantom – a disfigured vestige of his former self.

Swan has an obsession with trends and faddish technologies; for example, he gives Leach’s stolen music to the Juicy Fruits, a saccharine boy band whom Leach despises for their lack of artistic integrity. Leach massacres the Juicy Fruits by implanting a bomb in the carbonator of their muscle-car set piece. Here, Leach uses technology against Swan – music, technology, and horror convolve in order to create a shocking sequence of death and destruction.

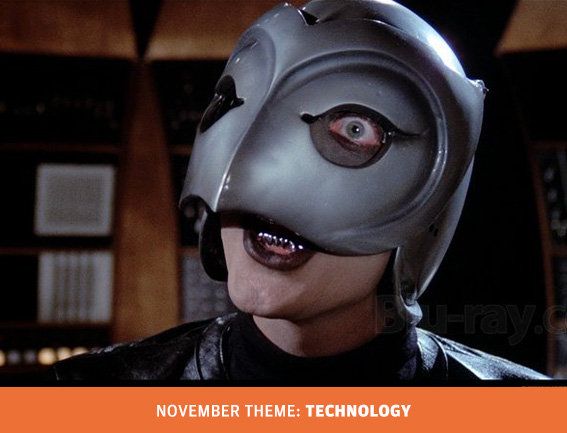

Later in the film, Swan allows Leach to speak (his vocal chords became damaged along with his other psychical deformities) again by using a kind of pitch alternator. The technology here allows the Phantom-Leach to speak and sing again; his voice is still monstrous, however, which allegorises technological terror once more.

The film’s nature as a technological time travelling device is perhaps best evidenced through its literary stimuli, most notably the characters of Dorian Gray and Doctor Faustus. Swan acts as an analogue to Dorian Gray, selling his mortal soul for immortality. Instead of a picture or portrait, however, the object which harbours Swan’s soul is a videocassette tape.

Leach eventually attempts suicide in order to escape his perdition. However, Leach signed a contract earlier in the film that bound his soul to Swan’s. The two men’s souls being connected through technology again highlights the anxiety surrounding technology in the 1970s. Leach destroys the videotapes and renders Swan mortal again, which means Leach can kill him and set things right. By doing so, however, he also kills himself in the process. Leach vehemently disapproved of technology whereas Swan relished in it; both men ultimately end up dead at the hands of it.

The film is a gem of musical horror, one which would have been more popular if not for The Rocky Horror Picture Show being released a year later. De Palma’s film makes one thing abundantly clear (which rings true even more so in this day and age): technology can be terrifying.