We first see Anabel walking the halls of her palatial home impeccably dressed for the evening and wearing towering heels. She stumbles briefly. A subtle but distinct foreshadow of her imperfect perfect life, a preordained sense of future events.

Anabel (Susi Sánchez, the recipient of this year’s Best Actress Goya Award for her performance) abandoned her daughter Chiara (Bárbara Lennie) when the girl was 8 years old. Thirty-five years on, Chiara finds her mother and she has just one unusual request: to spend ten days together in a remote house in the mountains. The two protagonists deliver extraordinary, full-bodied performances, contained on the surface, simmering with tormented emotions beneath (which, at some point, they unleash through dance: Anabel on the sound of “Dream a Little Dream of Mine”, and Chiara on the beat of Nena’s “99 Luftballons”). The emotional disorder of a mother and a daughter who have been apart for so long, but who are forever part of each other. A mother and a daughter who challenge one another from their contradictory selves: Chiara’s defiance and Anabel’s arrogance and apparent security.

La enfermedad del domingo (Sunday’s Illness), directed and written by Ramón Salazar, is a haunting examination of an estranged mother-daughter relationship that avoids melodrama platitude. It is so beautifully crafted that there is a dramatic intention in each word and a narrative thread in each movement of the camera, in each frame, in each piece of clothing, in each beam of light or musical note. It is such a visceral and ravishing story that it stays with you, long after the end credits.

La enfermedad del domingo is not only one of the best films, and my personal favourite, of last year, but it is a strikingly beautiful film. Photography (Ricardo de Gracia), production design (Sylvia Steinbrecht) and costume design (Clara Bilbao) work like a whole to weave a thrilling visual narrative that takes you to an almost indeterminate, improbable time between past and future, to an eerie state of mind fueled by the picturesque countryside and by the painterly, dimly-lit interiors of the mountain cabin. Anabel has created a completely crafted exterior, but the perfection she designed from the outside hides an inner world marked by bruised feelings. And it is her clothes, probably more than any other element, that have a defining role in getting us on this journey with her, a journey of her retribution for the sins she committed as a young mother.

In my interview with costume designer Clara Bilbao (who has just received the 2019 Goya Award for Costume Design for La Sombra De La Ley), she reveals why she seldom talked clothes with director Ramón Salazar, why naming one of the costumes “Dark Vader” made perfect sense and why she chose a profession of story teller.

“It’s easy to find a vain person”, says Bárbara Lennie’s character, Chiara, when asked how she had found her mother, Anabel (Susi Sánchez), who had abandoned her when she was eight years old. How would you describe Anabel? What did you want her clothes to convey about her?

Anabel is an intelligent, proud and arrogant woman. She decided to change her daughter and her austere life for a new and sophisticated life surrounded by first class peers. Sunday’s Illness is about the hard journey of this woman who will be taking off all that crust of glamour that envelops her until becomes the mother and the woman she was so many years ago. A strong, risky and visible wardrobe was necessary for each step of this path. From the beginning we understood that this wardrobe could not be subtle but had to be audacious and narrative.

In Anabel’s first scene, when she is walking her somptuous home, dressed for the evening and wearing high heels, she stumbles briefly. It’s the moment that sets the tone for the film. You already sense that there is a hidden meaning to her clothes, to her “perfect” life. What is she wearing in that scene?

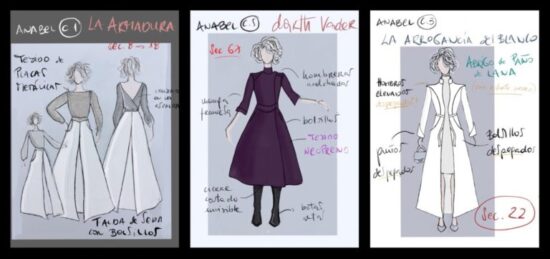

We call this wardrobe “The armour”. It is a two-piece gown composed of a white skirt of natural silk crepe with two bellows in the front and back that give it that light and elegant movement for the presentation of her home. However, the silver top is made from a fabric of small metal pieces that reminds us of those medieval meshes. We tried to get an elegant and sensual silhouette, but, at the same time, discover a character under an armour; someone who wants to protect herself from the outside, who does not show everything, who is not completely natural.

She then appears in this sculptural, imposing long white coat when she goes to meet Chiara at the hotel after their first encounter in her home. Throughout the entire film Anabel’s wardrobe seems almost too perfect. It almost makes you feel uneasy, it builds up tension and it helps the narrative tremendously. Like you said above, her clothes are like an armour. A façade to mask the turbulence beneath the surface. Is her life only empty wealth and beauty?

We called this piece of wardrobe “The arrogance of the white”. From the beginning, I imagined this wardrobe in white colour. White should mean purity and innocence. However, Anabel appears in front of her daughter as a cold, powerful and imposing figure, ready to show her strength, her determination and her untouchable status. To emphasise her coldness, I designed a coat with geometric lines, almost architectural, with a military look. We wanted Chiara to see in her mother a hard and impenetrable wall. Another armour. The idea was that this coat would end up being uncomfortable for Anabel and also for the spectator. We understand that Chiara does not let herself be scared by her mother.

What was the inspiration for Anabel’s wardrobe? Was the director, Rámon Salazar, who also wrote the script, a big part of the costume process?

Ramón Salazar and I have been friends for a long time. We know each other well and we have worked together before. This script impressed me a lot, especially because I had just given birth to my daughter 2 weeks before. As a mother, I thought it was a disturbing story with a huge force. To design a wardrobe, I need to talk to the director, listen to him. Ramón is an intelligent and sensitive director. He is bright and generous. He puts his total trust in his team and that is a wonderful incentive to work. His gift is the word and allows it to introduce you to his head and into the soul of the characters. But we do not talk about clothes in these conversations; we talked only about the characters. I witnessed the process of rehearsals with the actresses and that is a privilege for a costume designer. At first, Ramón had a more subtle idea for the costumes. But step by step I convinced him that we had to take a risk. In the fitting sessions he asked me: “Clara, are we crossing the line?” But he had confidence in me and the result touched him. That’s why we named some of the costumes; those names came out from the discussion of each sequence and each detail of the evolution of the characters.

Another example: the dress I designed for Susi in the sequence in which she washes Chiara’s hair is called “Dark Vader”. When I showed him the sketch and the fabric that I had chosen for this outfit, Ramón was not very convinced. He told me that it seemed dark and reminded him of Dark Vader. So I told him: “Perfect, Dark Vader is another bad father”, and that convinced him.

It is a privilege to create from the eyes of the director.

For me, it is also essential to work with the support of my team. My assistant, Maite Tarilonte, and the dressmakers have known me so well since a long time ago. I care about their opinion and their ideas. They make me feel secure in my decisions.

A costume designer’s job is to reinforce the story and help the actor form an identity of his/her character. But what exactly goes into the work of a costume designer today? All Susi’s costumes you’ve talked about so far were designed by you. How much ready-made shopping, how much vintage and how much making did the costumes in La enfermedad del domingo involve?

Susi’s wardrobe was exclusively designed and created for her. Each garment was drawn and custom-made. Only in the last part of the movie, Susi wears some used clothes that supposedly are not hers, that she had found in Chiara’s house. A blazer of her daughter, an old sweater, a raincoat, some rubber boots.

For Chiara’s wardrobe, we chose used clothing from the 80s and 90s.

The clothes, just as the entire aesthetic of the film, have a tremendous narrative power. When the two women arrive at Chiara’s home in the mountains, Anabel is wearing a beautiful wrapped blue coat. It stuck with me, because it seemed to blend with the surroundings and the austere decor in Chiara’s home. There is a great attention to details with every room, every piece of clothing, every shade of dark colour throughout the entire film. Sunday’s Illness has a distinctive look, it is such a visually beautiful movie. Undoubtedly, a collaborative work with the cinematographer and art director.

Of course it is; it is not possible to achieve a harmonious film that tells the same story if we do not work together with the artistic director, the director of photography and the makeup and hair styling team.

All the members of the crew were involved in the same influence of the director who managed to captivate us all in absolute communion. I admire the awesome work of Sylvia Steinbrech (production design), Ricardo de Gracia (cinematography), Ainhoa Eskisabel (makeup artist) and Sergio Pérez (hair stylist).

Even after she arrives in the countryside, in the first days, Anabel continues to wear rather inappropriate clothes, too elegant for the setting. Is this a way of trying to tell her and everybody else that she doesn’t belong there (the home she left many years ago)? Towards the end of her stay there, though, she finally changes into something more casual, like a well worn knitted sweater and jacket. She sheds off her armour. Is she starting to come to terms with the choice she made those many years ago?

We intended Anabel’s wardrobe to show her as a fish out of the water. Show a woman whose wrapping does not keep her safe from what awaits her. We pretended that she looks absurd and fragile in an environment that does not belong to her. But reality prevails and she finally takes off her armour to approach her daughter and go back to being the mother and woman she once was.

When she goes to Paris to meet her ex-husband, Chiara’s father, he makes a remark about her clothes, that she is dressed too lightly for the weather. She had taken a flight to Paris without planning, so her not being properly dressed for the cold weather is excusable. But that is not the point I want to make, nor her ex-husband. He goes on and says that Paris had never suited her and that they had to leave and live somewhere else. But that wasn’t enough either. And he continues by asking her if she had found what was looking for. She says she did, but adds that it was never enough. So I guess she had always tried to communicate something through her clothes, before and now.

On this trip to Paris, Anabel has completely left her shell. For the first time in many years, she makes a decision without thinking about herself. She doesn’t care about the cold, she doesn’t even care about the impression on her appearance that her ex-husband or any other person may have. She left with no more clothes than what she was wearing: used clothes that were in Chiara’s house. Anabel has been the main character of her story and now her daughter Chiara, finally, is the only object of her concern. From this new perspective, away from herself, Anabel can explain to her ex-husband, without inconveniences, the kind of life that she has left. Her inability to get satisfied. The inexhaustible vital gap.

There is another moment, on their way to the fest in the village, when Chiara asks her mother why she gave her an Italian name. Maybe I have watched too many films, also being a fan of Fellini and Marcelo Mastroianni, but I immediately thought of Chiara Mastroianni, Marcelo’s daughter, before Anabel starts telling her daughter about that actor from back in the day who always wore a suit and sunglasses. Obviously, she was inspired by someone famous in naming her daughter Chiara. Do you think it was because she was aspiring to that same kind of life? Was it part of her dream to be able to dress so elegantly every day of her life?

Anabel aspired to a movie star life. Sophisticated and remarkable. Nobody is surprised at that moment in the film that even the name of her daughter is inspired by the family of a movie celebrity. It seems that Anabel has always dreamed of living in a palace and dressing like princesses.

Chiara lives in the countryside and her casual clothes are, first of all, a reflection of her way of living. Jeans, worn-out oversized sweaters, coats and blazers, boots. But are her clothes trying to tell us more about her character? Does she use them as a way of hiding from the world because of what happened to her in her childhood?

She is a woman stuck in time. She never managed to recover from the abandonment of her mother. She became an introverted and lonely person. Chiara lives in a very small world, made on her own measure, surrounded by memories. Her whole world stopped when her mother left her that Sunday afternoon. We can imagine her rebellious and destructive youth. Some of all that pain survives in her clothes.

The only premise that Ramón gave to me for this character was that Chiara has not bought clothes in the last 20 years. All her clothes are more than 20 years old.

Yes, the feeling I got seeing Chiara in her clothes was that she seems so lost, as if her clothes, just like her life, do not belong to her anymore. But I would like to ask you something. I have been wondering about that time when Chiara is in Anabel’s house, together with the other waiters and waitresses, receiving instructions from Anabel before the grandiose dinner, before the mother realises who she is. Anabel asks everyone to take off every piece of jewellery they have on them. You don’t see Chiara’s face, but the camera shows her from behind taking her hand to the earring in her right ear without taking it off. Is she wearing just one earring? Is she wearing her mother’s jewellery? Why doesn’t she take it off?

This earring is the one that her mother forgot on the table at home on the Sunday before leaving forever. There is a short film titled El domingo (Sunday) that works as a preface for the Sunday’s Illness film and takes place on that Sunday when Anabel left.

I couldn’t find it with subtitles, but you can watch it below.

Chiara doesn’t take it off because she is defiant by nature. She has no fear of Anabel and does not intend to obey her mother at this point in her life.

Bárbara Lennie and Susi Sánchez are incredible actresses and are incredible on the screen together in this film. They inhabit their roles with the same ease with which they inhabit their clothes. Do you usually collaborate with the actors on the costumes? How was it in this case, with Bárbara and Susi?

I need to talk to the actors about their characters. That helps me a lot and expands my point of view and I put myself in their place.

If I could, I would work in all my films with Susi and with Bárbara. I admire them deeply as actresses, but especially as human beings. I think the whole crew learned from their professionalism, their partnership and their humility.

Seeing your fascinating work in La enfermedad del domingo reminds me of the fact that contemporary costume design does not get the attention it deserves. How do you feel about that? And what do you prefer, contemporary or period costume design?

I prefer the films in which my work is relevant and defining in telling the story. It is true that the historical films are usually more fascinating in a visual way and more enriching for a designer. However, I prefer the stimulating scripts and to work with directors like Ramón Salazar, for whom my work seems to be a fundamental piece to put their story on.

I feel sorry that the value of this kind of work is often unnoticed by the majority of the viewers. I have been so excited by the deep analysis you have done to my work. It’s unusual, I assure you.

Thank you. I am a fervent proponent of costume design as one of cinema’s most far-reaching influences and I am saddened that contemporary costume design is often not acknowledged as it should be and that many overlook the fact that in a good movie, nothing is left to chance, not even a plain t-shirt or an oversized coat. Clara, on an end note, what inspired you to become a costume designer?

I envy people with a vocation. I never had it. In fact, I wanted to be an airplane pilot, because traveling has always been the closest thing to a vocation for me. The school which I was supposed to enter disappeared overnight and my future plans collapsed.

My mother has been a haute couture dressmaker and I am lucky that she continues to work with me hand in hand in my costume atelier. She is the great reference of my life on many levels. The clothes, the fabrics, the designs have been part of my vital decor since I was born. Since my sister and I were girls, my mother used to allow us to choose the fabrics and the style that she sewed for us. So it was not so crazy to study fashion design as an alternative to being an airplane pilot (!!).

However, very early on I realised that Fashion did not really interest me. I found it difficult and boring to design costumes without an object. Fashion created directly for a concept and not for someone real.

I had fun disguising the whole neighborhood though, my cousins, friends… I always liked to read and also write and tell stories… When I met Diana Fernandez and Derubín Jacome, my teachers of Scenic Costume, a new horizon opened before my eyes. They are a Cuban couple, a costume designer and an artistic director respectively, with a brilliant and well recognised professional career. They told me about their profession, their films, their travels, their characters… I thought there could not be a better profession than the one that combined as a cocktail the stories, the characters, the costumes, the emotion…

Today I feel lucky. I am happy with my work despite how hard it is because it fills my concern to tell stories and to contribute my personal vision to each costume that I design. I feel privileged because every film I make contains something from me and it would be different if it had been made by another costume designer.