On paper, writer-director Lars von Trier and cowriter Niels Vørsel’s The Element of Crime (1984) is straight out of a 1940s-era noir. In the film’s opening, a mentally unstable detective named Fisher (Michael Elphick) is summoned to Europe to track down a notorious child-killer (echoes of Lang’s M here) known as Harry Grey.

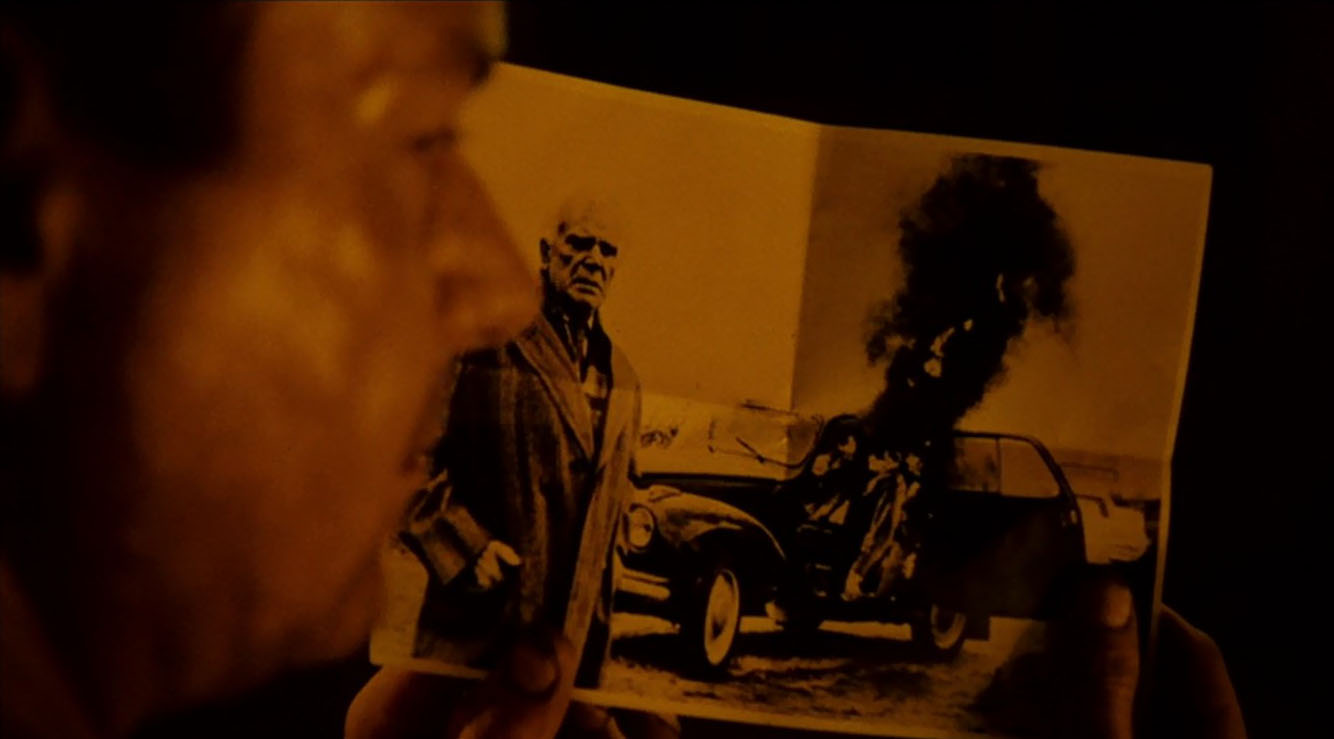

According to Osborne (Esmond Knight), Fisher’s delusional mentor, Harry Grey is dead. Is this, then, a case of a copycat killer? Who is Harry Grey, anyway? The audience never clearly hear or see him, and the only real ‘evidence’ of his existence is a grainy photograph of a burning car, the supposed scene of his death.

Those looking for clear-cut answers to these questions will be sorely disappointed. The noir-infused plot is secondary to the disquieting, surreal atmosphere permeating every scene. Trier is more interested in using this fairly routine detective story to upend the audience’s expectations and immerse them in a distinct, Kafkaesque world.

The film’s title itself is telling; it is not The Element of a Crime or Element of the Crime, but The Element of Crime, as if crime itself is a physical building block of the world, just as fundamental to human existence as water or air.

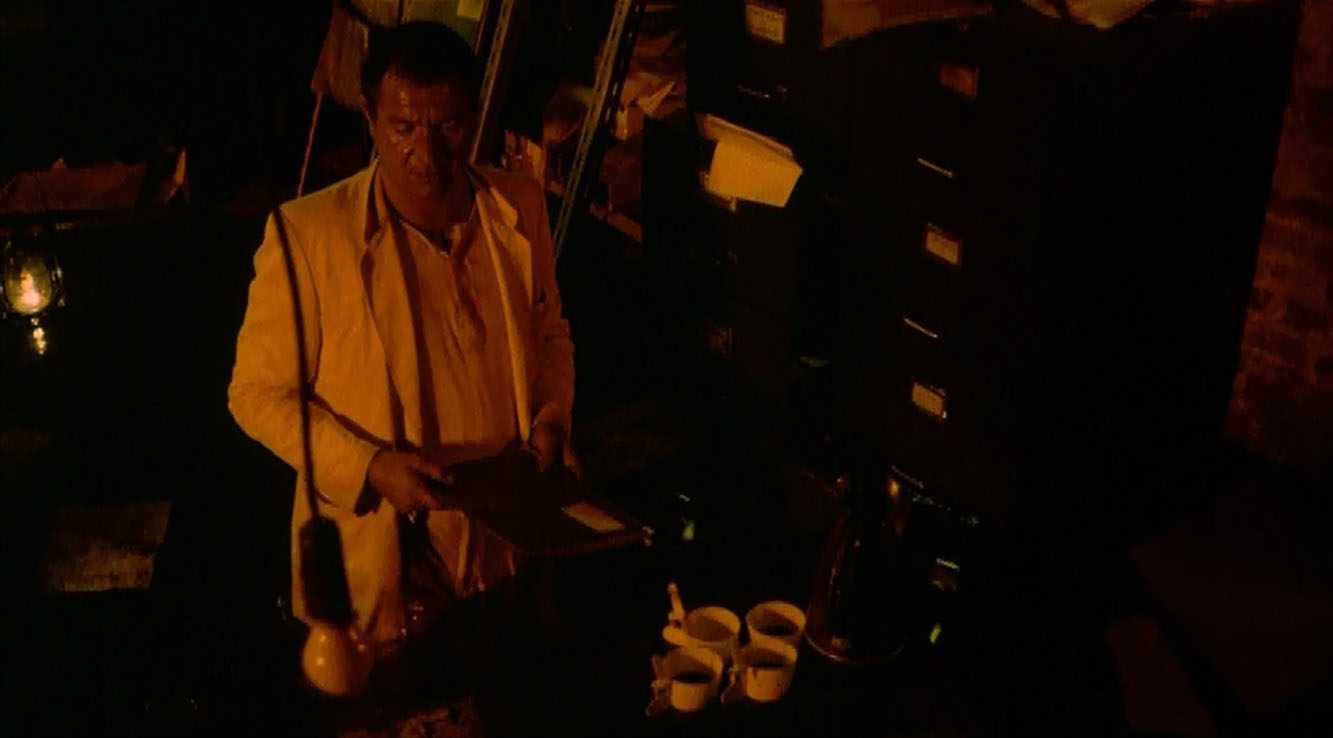

Indeed, the environment plays a key role in the film, perhaps the most important role. Trier’s vaguely futuristic Europe is a place of physical decay and constant, unrelenting rain; even indoors, water drips down the walls and, in one extreme case, waterlogs a police station’s archives department so that Fisher has to wade waist deep in water to retrieve Grey’s case file.

Most interestingly, this world also exists in a state of perpetual nighttime. Not a single scene occurs in daylight. “Is it always as dark as this time of year?” Fisher asks Osborne’s assistant. “There are no seasons anymore,” she responds. “The last three summers haven’t been summers.” This engaging fusion of noir and science-fiction tropes predates Alex Proyas’ Dark City (1998), which also takes place in a world devoid of daylight.

Despite its experimentalism (much has been written about its arresting, sepia-toned cinematography), The Element of Crime is one of Trier’s most accessible works. Unlike his recent output, which tends to open strong but slowly descend into numbing self-seriousness (Melancholia), Trier’s feature-length debut is a streamlined blast of visual inventiveness.