Architecture, like film, acts at many scales. Suspense cinema in particular exploits this superbly, beginning with the smallest – the room. The four walls which surround us for most of the day are our world for those hours. But as much as they are just walls, they are also screens on which we project our lives, our dreams, our fears.

Hitchcock understood this better than most and all three plague the main characters in Rope. Its carefully realised Manhattan penthouse setting reflects this and is critical to building tension.

The progression from entrance hall via kitchen and dining room to drawing room with vast picture window overlooking the city symbolises the aspirations of its self-actualising protagonists. At the same time such a limited space evokes claustrophobia and suggests the dead end ahead. The rooms are planned en enfilade, that is, in a row with doors aligned, entirely proper architecturally but also a useful enabler for Hitchcock given his desire to film in long takes and the relatively immobile cameras of the day. His shots makes full use of the entire suite, sometimes roaming, sometimes staring, sometimes following, sometimes waiting.

Hitchcock’s exploitation of a single tightly-managed room was expanded to the multiple rooms explored vicariously by the wheelchair-bound James Stewart through his Rear Window. Here, each of the dozen apartments opposite becomes a miniature stage, one room deep, on which a dozen individual dramas are played out. The theatrical comparison is apt since all of this was built as a vast indoor set, an adjustable backdrop echoing the time of day and the actors directed through earpieces. As with a stage, or a doll’s house, these spaces resemble reality but are designed entirely to aid the person telling the story. They are also analogues for the characters.

Thus the implacable prime suspect’s windows are severe and steel-framed, typical of a real inter-war building. They give the viewer the most access, sitting room and hall glimpsed through multiple apertures like a frozen zoetrope. The openness of the song writer’s generously-glazed terrace, meanwhile, becomes a metaphor for his romantic nature. Conversely little of the old married couple’s flat is seen and nothing of the extrovert sculptress’s anachronistically-columned home, balconies displaying the comedic action in both cases.

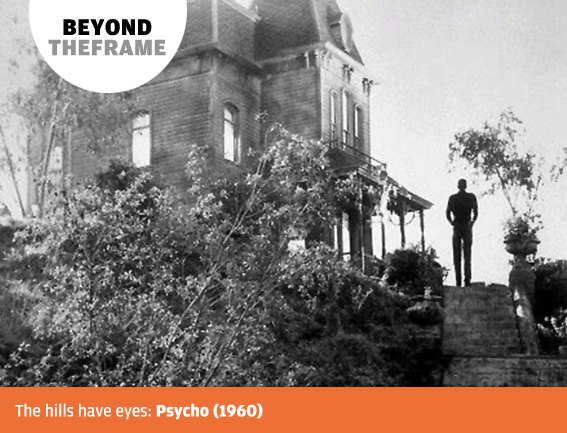

Hitchcock scaled up his architectural canvas once more with Psycho. The Southern Gothic of the Bates Motel, with its looming tower and deep dark attics, hints at the horrors within. The building even resembles a drawn, skull-like face. Inspiration for its design came from Edward Hopper’s painting The House by the Railroad, but the film goes rather further than the placid mood of that image.

The potential of the single building as a locus for anxiety and terror has been grasped by many directors since.

In Panic Room the hulking New York ‘townstone’ bought by Meg Altman is a true character, with as many contradictions as its human equivalents: solid but fragile, reliable but with flaws. In the viewing sequence the realtor helpfully explains its layout whilst Kristen Stewart’s actions illustrate it, a smart solution to a common narrative problem that further brings the building to life. In an appealing echo of Rope and Rear Window the entire house was constructed as a life-size, multi-level set on a sound stage, though David Fincher wittily dematerialises this highly crafted illusion by also flying a virtual camera through CGI walls.

Of course the old dark house trope is at work in all of the above, but two films demonstrate how even the transparency of glass architecture can be neatly subverted in service of a similar aim.

By the 1970s a gleaming new skyscraper was the image of the American city, whether the World Trade Center above New York, the Sears Tower dominating Chicago or the Transamerica Pyramid spearing the sky over San Francisco. In Irwin Allen’s The Towering Inferno a glittering glass stiletto of a tower rises from a facetted podium, this unseen in the final film but hinted at in the sets for Robert Wagner’s office. A man’s greatest achievement is about to become his biggest nightmare. A dozen years later, a second shimmering tower epitomises the success of one group before being plundered by a second in John McTiernan’s ground-breaking Die Hard. Here the real-life offices of Twentieth Century Fox stand in for the fictional Nakatomi Plaza.

Both films integrate their drama with the components of their settings. In each glass walls are initially as unyielding as stone for those trapped inside, whilst even the roof offers no escape. There are vertiginous views down a bottomless shaft, and lifts assume a critical role.

Whatever their style most buildings stand on streets. These, too, provide an effective tool for suspense.

When Snake Plissken flies over the once-bustling streets of Manhattan island in Escape from New York, the now darkened and decayed buildings laid out below set up an immediate jolt of dissonance. On the ground within the city-turned-prison, rowhouses with shuttered windows, bridges clogged with ruined cars and street after street strewn with rubble and fires symbolise once-familiar neighbourhoods turned upside down.

Set in the same city and again playing with notions of permanence and the threat of the other is Wolfen, beginning with a hauntingly powerful opening sequence in which a church emerges from billowing dust clouds as slums are razed around it. Old reassurances evaporate and the streets are now places of fear, stalked by members of a new species. That the church is revealed to contain their lair adds an ironic twist, whilst one victim is a property developer whose new buildings are, once more, depicted as a threat, this time to the titular creatures.

The room, the building, the street: three scales at which film and architecture interact, illustrated to perfection in Halloween. In compressing its action from a street to a block to a house to a room to a closet before a sudden release, John Carpenter deftly demonstrates an idea fundamental to both disciplines. Hitch would be proud.