When I began working on Akira Kurosawa, the pivotal role for his cinema of Toshiro Mifune (b. 1 April 1920 d. 24 December 1997) sprang immediately to mind. I could not help thinking how much Mifune’s presence and vitality contributed to the strong sense of movement in Kurosawa’s films. Mifune’s intense acting already fascinated the Japanese public in his first film, Senkichi Taniguchi’s Ginrei no hate (Snow Trail, 1947). He had also fascinated Kurosawa, the co-writer of Taniguchi’s film, during their first meeting at the New Faces Contest for young actors organized at the Toho Studios in 1946.

Between 1948 and 1965, Mifune appeared in sixteen films directed by Kurosawa, who understood and made use of Mifune’s outstanding talent better than any other director. His tremendous expressive capability made him the perfect actor for Kurosawa, the filmmaker preoccupied with movement. With Mifune, he had found the ideal actor – intelligent and creative and also able to inspire films with his incredible energy, versatility, sense of rhythm, and charisma. The following remark by Kurosawa’s long-time collaborator Teruyo Nogami is by no means an exaggeration: “Without Toshiro Mifune, the films of Akira Kurosawa could never have come into being.”

Drunken Angel

Drunken Angel

Kurosawa avoided typecasting, allowing his protégé to demonstrate a wide range of performance skills. In their first three films, Mifune was cast as a yakuza (Drunken Angel/Yoidore tenshi, 1948), a police officer (Stray Dog/Nora inu, 1949) and a doctor suffering from syphilis (The Quiet Duel/Shizukanaru ketto, 1949). The nervousness of the young rebellious gangster in Drunken Angel prefigures shattered masculinities explored by Hollywood cinema in the 1950s, and the laconic ronin in Yojimbo (Yojinbo, 1961) created a new type of hero – powerful and at the same time disenchanted – which became a prototype for Japanese and Western cinema. As Kikuchiyo (Seven Samurai/Shichinin no samurai, 1954), the peasant who pretends to be a samurai, Mifune expresses the most contradictory feelings through an acting style based on overstatement, which also distinguishes the character he plays from the six samurai and serves as a reminder of Kikuchiyo’s humble roots. Although overstated, Mifune’s multifaceted performance creates moments of great subtlety, thereby revealing Kikuchiyo’s inner torment.

Mifune’s more restrained performances in The Bad Sleep Well (Warui yatsu hodo yoku nemuru, 1960) and High and Low (Tengoku to jigoku, 1963) contrast with his extravagant facial expressions and body language in Seven Samurai and Rashomon (1950), creating complex characters by means of finely nuanced acting. In The Bad Sleep Well, a pair of glasses and Mifune’s ability to disappear behind a mask transform the character he plays into a man with no distinguishing features. In Record of a Living Being (Ikimono no kiroku, 1955) it is not simply make-up and white hair that make thirty-five-year-old Mifune credible as a man twice his age. Nakajima’s posture – bowed down by age – and the vacant expression behind the lenses of his glasses also contribute superbly to this impression. Close-ups serve to highlight the great variety of complex facial expressions.

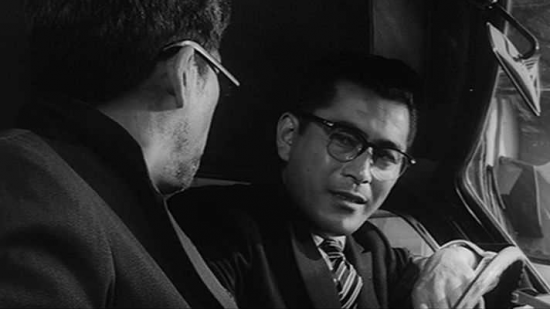

The Bad Sleep Well

The Bad Sleep Well

Mifune’s penchant for movement and his tremendous vitality are perfectly channeled through objects: cigarettes (Drunken Angel), a lighter (The Quiet Angel), cigars and matches (The Idiot/Hakuchi, 1951), a fan (Record of a Living Being), a toothpick (Yojimbo). Kurosawa knew how to keep his star’s hands busy and at the same time to add movement to the images created in this cinema obsessed with detail. The way Sutekichi rolls up the sleeves of his kimono or chews on his toothpick to express his boredom introduce movement to otherwise static shots (The Lower Depths, 1957). In this film, Mifune’s energy is perfectly measured – not completely suppressed but, because of the contrast with the setting, highlighting (through his presence and performance) the abjectness of the tenement and the hopeless situation of its inhabitants.

His collaboration with Kurosawa is at the core of Mifune’s rich and long career, during which he appeared in over 150 films produced for the cinema and for television in and outside Japan. He frequently worked with Hiroshi Inagaki, Kihachi Okamoto, and Senkichi Taniguchi. His interpretation of Musashi Miyamoto in Inagaki’s Samurai trilogy (1954-1956) about the legendary swordfighter of the seventeenth century presents Musashi as a combination of vulnerability and determination. Musashi’s journey towards maturity and his quest for perfection is paralleled by Mifune’s roles from tormented youth to the reaffirmation of masculine strength.

Seven Samurai

Seven Samurai

As an actor, Mifune is closely connected with the figure of the samurai, which he played in numerous films, but he is also convincing as a romantic lover in Keisuke Kinoshita’s Wedding Ring (Konyaku yubiwa, 1950) or in Mikio Naruse’s Conduct Report on Professor Ishinaka (Ishinaka sensei gyojoki, 1950). His performances as a military figure – another role in which he was frequently cast in the 1960s – avoid stereotyping by revealing the human face of historical figures such as Admiral Yamamoto (Admiral Yamamoto/Rengo kantai shirei chokan: Yamamoto Isoroku, 1968, Seiji Maruyama) or General Korechika Anami, the last War Minister before Japan’s capitulation (Japan’s Longest Day/Nihon no ichiban nagai hi, 1967, Kihachi Okamoto).

It would certainly be misleading to want to reduce Mifune’s acting skills to the style of the tateyaku, the young, energetic hero of kabuki theatre. His performances are – consciously or unconsciously – influenced by many sources, to which the actor added his personal talent and inventive spirit, his charm and his sensuality. There is naturalism as well as stylization – sometimes in the same film (as in Seven Samurai), and Mifune was at ease with both. He was also blessed with great comic talent. In Daredevil in the Castle (Osaka-jo monogatari, 1961, Hiroshi Inagaki) or Red Lion (Akage, 1969, Kihachi Okamoto), Mifune explores farce and more sophisticated forms of humour, creating hilarious moments. Even in somewhat conventional but highly entertaining television productions such as Ronin in a Lawless Town (Muhogai no suronin, 1976), his sense of humour and ability to suddenly adopt a very different facial expression save the characters from being mere clichés.

Yojimbo

Yojimbo

Yojimbo challenged the rather conventional masculinity of Inagaki’s Musashi in his Samurai trilogy. Mifune, who had founded his own production company in the early 1960s, explored the role of the laconic, disenchanted super-samurai created in Kurosawa’s Yojimbo and Sanjuro (Tsubaki Sanjuro, 1962), in Zatoichi Meets Yojimbo (Zatoichi to Yojinbo, 1970, Kihachi Okamoto), Ambush at Blood Pass (Machibuse, 1970, Hiroshi Inagaki), and in several television series. His performances also display an interest in social criticism – denouncing intolerance, repression and social injustice.

In his last film, Kei Kumai’s Deep River (Fukai kawa, 1995), Mifune, already marked by illness, plays his small supporting role with incredible force, creating a profoundly moving figure. The inner flame and the desire to perform were still very much alive.

3 replies on “Toshiro Mifune – Intense acting and inventive spirit”

Pity you do not mention ‘Hell in the Pacific’ (1969) by John Boorman, starring Lee Marvin and Toshiro Mifune.

Two great actors carrying the entire movie, meeting in wartime as enemies and forced to work together in order to survive.

Much underrated.

And Red Sun with him and Charles Bronson

He was also in Zatoichi Meets Yojimbo with Shintaro Katsu as Zatoichi.