William Wyler’s The Best Years of Our Lives concerns the fraught homecoming of three servicemen at the end of WWII, and the difficulties they encounter reintegrating into American society. One of the many things that made this film special was the casting of Harold Russell as Homer Parish, a sailor who has lost both his hands and had them replaced with maneuverable metal hooks. Whereas today this effect might be slickly achieved using CGI, the 1946 film used an actor (Russell himself) who shared his character’s particular war wound.

These hooks come to represent many things. First and foremost they stand as potent symbols of the horror and losses resulting from the war: Homer’s mother recoils tearfully the first time she sees them; local children spy on him as the neighbourhood freak, prompting the disturbing moment when he lunges the hooks through a window, yelling “Take a good look!” Yet they also demonstrate American ingenuity and the ability to pull through in tough times. Wyler repeatedly lingers on Homer adeptly carrying out manual tasks: lighting a cigarette, using an air rifle, even playing a piano – often after having to dissuade onlookers from stepping in to help. These moments have a power that transcends the fictional: we are aware of watching a real person who genuinely has had to learn how to do these tasks anew, just as his country was having to relearn how to live a normal life.

Perhaps most touching, though, is the role the hooks play in Homer’s relationship with Wilma, the sweetheart he left behind, played by Cathy O’Donnell. Homer makes clear on the plane home that, more than anything else, he worries how Wilma will cope with his disability: “I’m alright,” he says, “but… Well, you see: I got a girl.” Yet it becomes clear that it is he and not she that stands in the way of their happiness, having convinced himself that no one could want to stay with him out of anything other than pity. Wilma finally dispels this fear when she accompanies Homer to his room to see what happens when the hooks come off, revealing the stumps: the true, painful lack which all the new dexterity hides. Wilma rises to the occasion, buttoning up his pyjamas and straightening his collar – a dress rehearsal for the marriage bed to come. The couple’s embrace here is made all the more poignant by our memory of Al (Fredric March) having earlier noted sadly that, despite all they’ve done for him, the Navy “couldn’t train him to put his arms around his girl”.

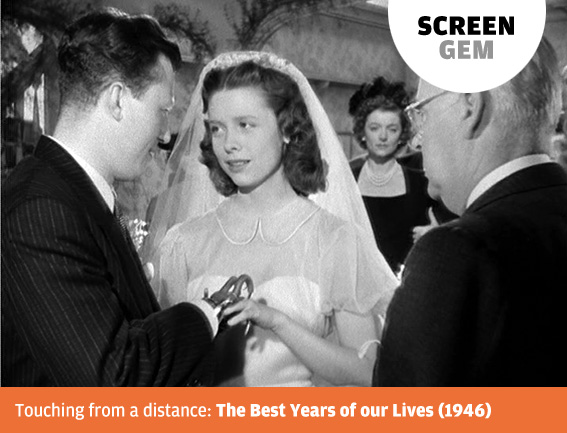

In the film’s final scene Homer and Wilma marry, the moment of reckoning loaded with significance prior to the placing of the ring upon the bride’s finger. The congregation tense up as they watch Homer attempt this simple, symbolic action. The task completed, Wilma makes her vows whilst holding the metal prosthetics which Homer now calls hands: an indelible image of a country carrying on, despite its hurt.