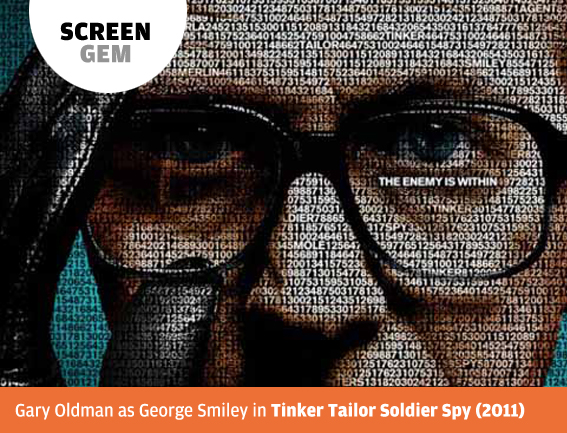

When Daniel Craig strode out of the surf wearing those blue swimming trunks and announced himself to the world as the new James Bond, Martin Campbell’s Casino Royale (2006) became an instant hit. With Gary Oldman’s first appearance in his heavy, horn-rimmed spectacles in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, the visual appeal is more muted but, in its own way, no less powerful.

Tomas Alfredson’s superlative adaptation of the John le Carre espionage novel is a beautifully designed and crafted 1970s period piece, centring on Oldman’s George Smiley and his search for a “mole”, or undercover Soviet agent, at the top of the “Circus”, or MI6 (based in London’s Cambridge Circus).

The glasses say a lot. Flashbacks to Smiley in nattier, tortoise-shell specs immediately seem wrong once we see the more traditional horn-rims – they sit imperiously on that impassive face, a barrier between Smiley and the audience, posing the question: Just what has this man seen in his decades in the spy game?

Early in Alfredson’s picture, Smiley visits an optician and exits wearing his immediately comfortable, instantly iconic goggles, a visual representation of his quiet mastery, his measured morality, his calm maturity – more Harry Palmer than Harry Potter, but more Puritan than Michael Caine’s Palmer. More Guinness – Arthur, not Alec – than Vodka Martini, shaken or stirred.

Oldman’s Smiley deals in silences. His interrogation technique involves a lot of listening, and a minimum of actual inquiry. His voice – based on le Carre’s own, Oldman says – flatlines through the picture until, just once, it goes up a notch. The amplification stops short of 11 – it’s a more subtle change, maybe from five to six, seven at most. But the effect of this sudden deployment of the volume control is diamond sharp and devastating.

Smiley does not lose the rag – there is no need for him to smooth his hair, to replace or even realign his glasses. His focus is sharp once again, and all is right with the world.

Or is it?

Alfredson (Let The Right One In), and screenwriters Peter Straughan and the late Bridget O’Connor, have not only successfully distilled a complicated novel into two hours – the much loved and memorable 1979 TV series ran for five hours – but have also captured and conveyed the melancholic, bittersweet feeling of the end of an era, the changing of the guard, for better and for worse. Every location, exteriors and interiors, every wardrobe and prop choice, every beat of the film-makers’ art, help remind us this is a different time, a different world, that we will never see in quite the same way again.