In Kwaidan, Masaki Kobayashi adapts four Japanese moralistic fairy tales retold by the Greek-American expatriate Lafcadio Hearn in the early twentieth century. Mirroring each other, the four episodes present a carefully structured series of repetitions and counterpoints. Their protagonists are haunted characters who face the unknown while struggling with a traumatic past or a present crisis.

“The Black Hair” tells the story of an ambitious samurai who is unable to understand the value of love. The scene in which he discovers that his wife, to whom he thought he had made love the previous night, has turned into a skeleton creates a moment of horror. However, the film evokes the uncanny through a surreal atmosphere rather than through shock elements or special effects.

The strangeness of the house, which has fallen into ruin and which nature has repossessed, draws the viewer into the realm of the fantastic. The gloomy setting is the perfect expression of a haunted place, linked to death and decay, themes which are at the core of this story and which reappear in the other episodes.

Natural elements – snow, ice and mist – invade the interiors in the second and third episodes, revealing spaces marked by the supernatural. The artificial setting, including a painted background, as a means to create an atmosphere of the fantastic, is especially elaborate in “The Woman of Snow”. In the scene in which the woodcutter and his future wife first meet, the sky is painted orange and pink, colours matching the woman’s pink kimono.

The reappearance of the female spirit plunges the scenery into a cold, bluish light which contrasts with the warm colours of the woman’s very human appearance with its evocation of love and happiness. Her metamorphosis into an evil figure is accompanied by an eerie sound created by Torū Takemitsu, whose music score contributes very effectively to the emergence of the fantastic throughout the film.

In “Hoichi the Earless”, the distance to reality is created via several levels of aesthetic abstraction. A few shots of nature – the coast where the famous battle of Dan-no-ura took place in 1185 – contrast with highly stylised scenes of the battle and with those in the ruins of the castle where the spirits of the Heiké samurai listen to the biwa player, both situations being recreated on a sound stage.

Elements of Noh theatre are evoked by the choreography and the way human figures are positioned in the space. The stillness of the bodies, supported by the slow movements of the camera, intensifies the feeling of a world beyond reality.

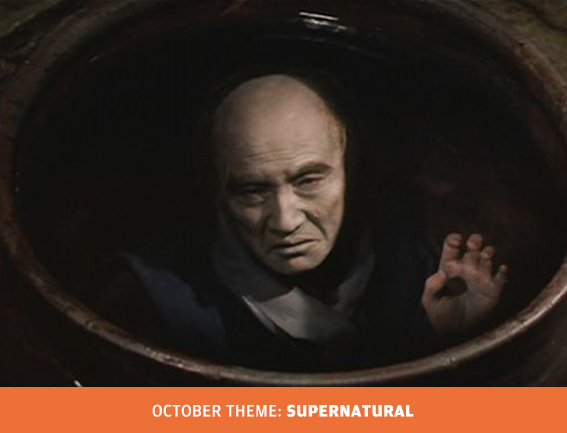

“In a Cup of Tea” links the process of writing with the story told by the writer who, not unlike the samurai in his tale who swallows up his soul, becomes the victim of a mysterious force. The samurai drinks the water in which the face of a man has been reflected and goes mad. The writer, who has tried to apprehend the mystery, is forever imprisoned in a state of horror.

According to Japanese ghost lore, these characters share the fate of all human beings who spend too much time in the company of spirits: the samurai in “The Black Hair” becomes senile before our eyes, the snow woman spares the life of the woodcutter but remains a constant threat to him and his children, the ears of the blind Hoichi are ripped off in exchange for his life.

Reality and illusion merge constantly, whereas the spirits, rather than being mere harbingers of fear, bring self-knowledge to the living. Kobayashi points to the fragility of human existence and mankind’s ultimate powerlessness. However, there is a glimpse of hope when Hoichi decides to play the biwa without knowing whether his audience is truly human: “I’ll play to console those sorrowful spirits and ensure that they rest in peace.”