How does one go about choosing the best films of the year, let alone of the decade? Several of our regular contributors took on this daunting task, and the eclectic results attest to ten years of remarkable films. Share your favorites with us @BigPicFilmMag.

2010

13 Assassins (Dir. Takashi Miike)

A group of assassins, 13 in fact, band together to take down an evil warlord. They must take on his army of henchmen to do it. Plot over, let’s get to it. Incredible stunts, incredible choreography, incredible violence. This is ecstatic action cinema, with an attention to set pieces and mounting excitement that is a joy to behold.

-Neil Fox (NF)

The Arbor (Dir. Clio Barnard)

Clio Barnard’s film about playwright Andrea Dunbar (1961-1990) combines documentary elements with excerpts from her plays performed outdoors in Bradford, where she grew up. Past and present, reality and imagination come together in this approach to Dunbar’s short and tragic life. The result is a rich portrayal of a tormented soul and of life in the margins of society, the stuff of which British Kitchen Sink Realism was made and which inspired the “Cinema of Social Conscience” represented by Ken Loach, Mike Leigh, Alan Clarke and others. The multiple layers of meaning in this film infuse realist and critical cinema with a new freshness and formal richness.

-Andrea Grunert (AG)

Cold Fish (Dir. Sion Sono)

The tension in Cold Fish is not linked to a criminal investigation but to the rise of aggression that drives a shy and ordinary man to commit murder. Sion Sono depicts Japanese society as hypocritical and corrupt. Respectability is only a façade behind which fantasies of power and violence are played out. Depravity lurks under a thin layer of courtesy. The framing and editing create a claustrophobic atmosphere in which the deprivation of space underlines the protagonist’s loss of power. The peaceful shots of aquariums contrast with the gory violence of other scenes, the variations in pace matching changing psychological states that the acting supports marvelously.

-AG

Inception (Dir. Christopher Nolan)

In the 2010s, films like Inception became an endangered species. Whereas other high-minded big budget sci-fi of the aughts, such as Edge of Tomorrow and Annihilation (also great examples of the genre from the decade), underperformed at the box office, audiences responded to Inception like it wasn’t a mind-bending rumination on time, loss, memory and all the other big ideas Christopher Nolan was mulling when he dreamt up the film. Anchored by Leonardo DiCaprio in movie star mode, playing the chief of a team of hi-tech thieves infiltrating energy heir Cillian Murphy’s dreams, Inception is otherwise one of the weirdest and most cerebral blockbusters ever made, and all the more glorious for the fact that its director still managed to make it accessible to so many people.

-Brogan Morris (BM)

The Other Guys (Dir. Adam McKay)

Director Adam McKay pivoted with this 2010 comedy, a film that is both straight comedy and also political and social commentary. It’s also the last film where he really did what he is great at, which is directing comedy. Will Ferrell and Mark Wahlberg display incredible timing and chemistry in this tale of two cops for whom the periphery isn’t far enough away – for different reasons – who find themselves crawling and bumbling towards the big time. Around the central pair are amazing turns from Michael Keaton as their sarge (who also works part time at Bed Bath and Beyond) and Samuel L. Jackson and Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson as the pinnacle detectives in the force. The latter gives one of my favourite comedy line readings of all time when asked by a reporter following a major arrest if he is dating Kim Kardashian. One of many jewels in a riotously funny movie.

-NF

Valhalla Rising (Dir. Nicolas Winding Refn)

At the other end of the pace spectrum from 13 Assassins is Nicolas Winding Refn’s hallucinogenic, punctured odyssey where long, excruciating sequences of haunted death in the form of Mads Mikkelsen’s cursed crusade knight, are punctuated by respite in the form of extreme medieval violence. This is action cinema inverted by a master subversive but one that still moves inexorably towards a deranged denouement. Some of the most thrilling images, visuals and sequences of violent rage in the movies this decade.

-NF

2011

Oslo, August 31st (Dir. Joachim Trier)

Though he has proven himself quite the versatile filmmaker this decade, making both his English-language debut (Louder than Bombs) and an erotic, supernatural thriller (Thelma), Joachim Trier has yet to top this 2011 masterpiece. Trier and co-screenwriter Eskil Vogt cleverly transcend the inherent limitations of “a day in the life”-style narratives; in one virtuoso sequence, the camera steps away from recovering addict Anders (Anders Danielsen Lie) to explore the conversations and lives of strangers seated in a restaurant. Anders’ tragic story is one of many; the world moves on, as it must.

-Thomas Puhr (TP)

Kill List (Dir. Ben Wheatley)

Continuing in the tradition of the all-time great horrors, what terror there is in Ben Wheatley’s Kill List is so terrifying precisely because it’s so unfathomable. What is the meaning of the symbol that Fiona scratches onto the back of Jay’s bathroom mirror, and why does she follow him and fellow hitman Gal up north on their latest ‘work trip’? Why are Jay and Gal ordered to kill, among other people, a priest, and how is he connected to the snuff video Jay discovers in the warehouse? Just who are those naked cultists that attack Jay and Gal in the final act? The film doesn’t provide answers. Starting as a story of a misanthropic hired gun’s suburban ennui before evolving into a grisly folk horror, what pitch-black humour there is in the rest of Wheatley’s work is largely absent here, a dreadful portrait of underworld Britain.

-BM

The Story of Film: An Odyssey (Dir. Mark Cousins)

There are few better introductions – if a 15-hour documentary can aptly be called an introduction – to film as an art form than Mark Cousins’ The Story of Film. A comprehensive study of cinema history as well as a starter’s guide to the language of the medium as well as a recommendation list of obscure titles as well as a personal essay for Cousins, the film is both sprawling and exhaustive, factoring in movies from across the globe from the dawn of cinema to the modern day. If cinema can be called a religion for some, then this already looks like an essential text for the faithful cineaste-in-training.

-BM

2012

Amour (Dir. Michael Haneke)

Over four decades Haneke has been European cinema’s maestro of the morbid, yet in this deservedly Oscar-winning drama the director finds a subject matter that is utterly transformed by such saturnine contemplation. Veteran French cinema icons Jean-Louis Trintignant and Emmanuelle Riva are the elderly middle class Parisian couple of Anne and Georges, retired piano teachers (an occupation integral to Haneke’s conception of class) who have helped foster the talents of generations of concert pianists. When Anne suffers a series of debilitating strokes she leaves Georges in a position of care-giver, as he stubbornly holds to the promise he made his wife that he would never put her in to a care home. At this point love and death come so intensely close together on the screen that an unbearable emotional weight, ruthlessly devoid of the usual sentimental cinematic pitfalls, descends upon the empathetic viewer.

Much like in his directorial debut The Seventh Continent (1989), Haneke relies on placing his character’s under the relentless scrutiny of the camera. So many scenes within Amour stray into the uncomfortably voyeuristic that is the director’s express forte. Yet ingeniously Haneke unearths a filmic empathy by remaining as doggedly fixed on the death of this relationship, as the character of Georges is in preserving a sense of Anne’s independence and autonomy. What does love mean after all? Selfishness and cruelty are shown to be just as crucial constituent parts as sentiment and kindness. With the very last sequence of the film Haneke also underscores an overarching theme of the insularity of love, for here is an apartment space filled with all the things of a life shared, and this is as an inscrutable mystery to the couple’s daughter, played by a previous Haneke piano teacher, Isabelle Huppert.

-Rohan Crickmar (RC)

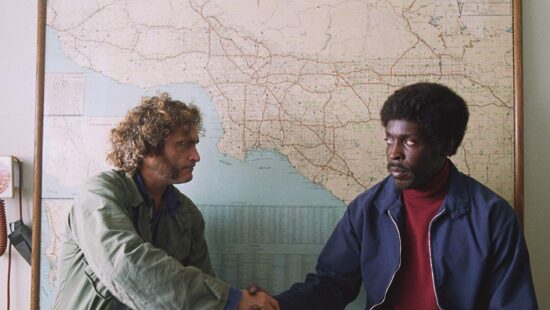

Killing Them Softly (Dir. Andrew Dominik)

Like a well-oiled machine, Andrew Dominik’s Killing Them Softly moves with breakneck speed toward its brutal ending. Many question the writer-director’s changes to the source material, George V. Higgins’ Cogan’s Trade, but he kept what’s most essential to Higgins’ style: the crackling dialogue, much of which is taken verbatim from the novel. This grossly underrated film was met with much disappointment, probably because people were expecting The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford’s poetic lyricism rather than the cinematic equivalent of being hit in the head with a brick. Brad Pitt is in top form here, and he delivers one of my favorite last lines in recent memory: “Now fucking pay me.”

-TP

The Master (Dir. Paul Thomas Anderson)

If the film is more meandering than the director’s 2007 masterpiece, There Will Be Blood, Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master is still the work of a filmmaker of immense focus – scored, shot, written and designed at the height of artistry, not to mention built around one of the most immensely realised performances of this past decade. Joaquin Phoenix, his actorly indulgences indulged by his 2010 mockumentary, I’m Still Here, returned to more straightforward narrative cinema ravenous-thin and laser-focused in Anderson’s post-war examination of masculinity, an intimate epic about religion, addiction and the endless search for fulfilment. With a Wellesian Philip Seymour Hoffman as a dueling partner, Phoenix – re-energised by his experimental ‘retirement’ – gives one of the great cinematic performances in a film aching with feeling.

-BM

Paranorman (Dirs. Chris Butler & Sam Fell)

This is a film that is so in love with cinema and its genre that it drips from every frame and out of each speaker. It’s a funny and thrilling collection of references and traces from across the horror and sc-fi spectrum, brought together by a sumptuous John Carpenter indebted Jon Brion score. What has made it last for me though, are its brilliantly progressive character representations for an early 2010s teen/family flick aligned with its passion for classic 80s action storytelling. It’s amazing how it doesn’t tip over into smug pastiche, but manages to maintain its joy and uniqueness and be a repeatedly rewarding adventure story experience.

-NF

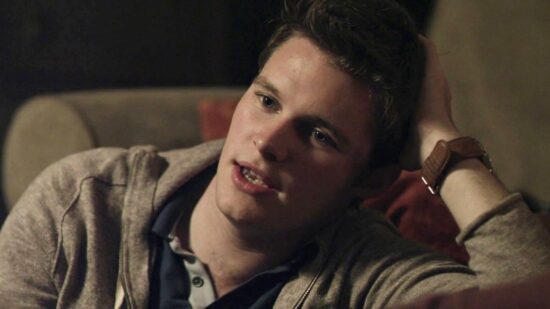

What Richard Did (Dir. Lenny Abrahamson)

What would you do if you accidentally killed someone in a drunken brawl, but nobody could prove it was you who delivered the deadly blow? That’s the horrible question posed by What Richard Did, one morbidly fascinating enough to keep us interested even though the accidental murderer in this case is an entitled teen whose greatest concern seems to be that the act could put the brakes on his golden boy trajectory to the top. Lenny Abrahamson’s film, anchored by an astonishing performance by a then-19-year-old Jack Reynor, is a mystery. We wonder whether Richard actually feels regret over what he’s done, or if his anxiety – crystallised in one shattering scene in which Reynor’s hyperventilating cries late one night quickly escalate into hellish shrieks – merely signals fear over the possibility of being caught.

-BM

2013

A Field in England (Dir. Ben Wheatley)

Ben Wheatley’s black-and-white film A Field in England constantly breaks the conventions of the historical and the war film and oversteps genre boundaries by including social conditions, power structures and human relationships. The field, the film’s central space, becomes a metaphorical place in which political, psychological and philosophical topics are explored in a way that is visually complex and sensual. The strangeness of the field, supported by sound and music, draws on the fantastic, and the film creates emotions which can lead to an understanding of and reflection on violence, war and oppression.

-AG

Hard to Be a God (Dir. Aleksey German)

Set on another planet that resembles our own, Aleksey German’s three-hour epic follows a group of scientists who are sent to a medieval village to rescue intellectuals. Not that this is particularly apparent: watching it feels like one of those dreams where your feet sink into the ground and unrelated events stack up like a totem pole. The village’s inhabitants live in squalor and mud, and seem to be perpetually bewildered and waiting for something – a renaissance? – that never happens. It’s nightmarish and anxiety-ridden, but it has moments of surprising beauty: fish scales shimmer on the corpse of a hanged man, mud and sweat glitter in the pale sunlight and mist drifts through bare trees, giving the village a barren eeriness. It’s not an easy watch, but you won’t forget it.

-Georgina Guthrie (GG)

Pilgrim Hill (Dir. Gerard Barrett)

This is one of those low-budget films which look as if nothing happens, but which continue to haunt the viewer long after watching it. Gerard Barrett depicts the rather dull life of an Irish cattle farmer, most convincingly played by farmer and occasional amateur actor Joe Mullins. Long sequences, a slow rhythm and the lack of non-diegetic music support the feeling of authenticity. It requires some skill to make effective use of this authenticity, but Barrett succeeds, creating moments of great intensity.

-AG

Stray Dogs (Dir. Tsai Ming-Liang)

Maybe my favourite older filmmaker that I learned about and ‘got into’ this decade was the mercurial Tsai Ming-Liang. His 2003 ode to cinema is easily one of my favourite films of all time and one of this decade’s pleasures was being excited for a new feature film at the time of its release by a filmmaker who works across diverse forms, media and durations. Stray Dogs tells the story of the lives of people in Taipei, and that’s it plot wise. The experience though is transcendent. The feeling the film conveys of life, time and space as inhabited by bodies, alone and passing, of structures built by and around and in spite of humans is something that isn’t easily shaken or forgotten.

-NF

Under the Skin (Dir. Jonathan Glazer)

Dressed up in a black wig, fur coat and red lipstick, Scarlett Johansson drifts through the damp Glasgow suburbs and Scottish Highlands in a white van. Occasionally, she pulls up by lone men and asks them for directions in a clipped English accent. If she likes them, she offers them a lift. Some decline and wander off. Others climb in and will soon be used as meat. Glazer’s disturbing horror is icy, lonely and atmospherically bleak – as is Mica Levi’s extraordinary score.

-GG

The Wolf of Wall Street (Dir. Martin Scorsese)

There’s just as good an argument to be made that The Wolf of Wall Street is a horror, not a comedy, its depiction of vampiric New York traders freely ruining lives for profit in an indifferent world as nightmarish as anything Martin Scorsese ever conjured up in his gangster pictures. But what’s truly remarkable about Wolf is how it sustains its comedy credentials over three hours, through slapstick, drugged-out comic setpieces, gross-out humour and some absurdly funny dialogue exchanges (“Let’s run like we’re lions and tigers and bears!”), all of it anchored by a Caligula-esque Leonardo DiCaprio in peak form. Made at the tail-end of a period where the bloated, improv-heavy Apatow comedy reigned supreme, the then-71-year-old Scorsese showed ’em how it was done.

-BM

2014

American Sniper (Dir. Clint Eastwood)

One can enjoy American Sniper as an effective action movie, but it contains enough elements to be an important anti-war film. Clint Eastwood explores the very idea of the American hero, showing Chris Kyle as an update of Dirty Harry Callahan, as a man who is a true professional but also a disturbed human being. Not unlike Fenimore Cooper’s Natty Bumppo, Kyle is the epitome of the American hero, a genteel man and a killer. Eastwood succeeds in combining skillfully filmed action scenes with moments of great intimacy. He makes use of action and other devices of the war film genre to reveal the contradictions which mark his hero and also the loss of innocence which tarnishes the American Dream.

-AG

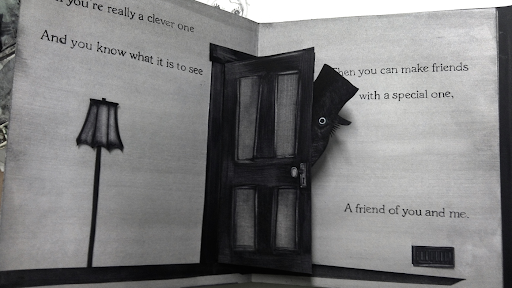

The Babadook (Dir. Jennifer Kent)

Jennifer Kent’s chilling debut tells the story of a character from a child’s book who comes to life and terrorises a small family. Or is it the imaginings of a woman gripped by loneliness and grief? Kent masterfully creates a claustrophobic, whispery, intimate atmosphere that not once relies on jump scares – and is all the more sinister for it.

-GG

Boyhood (Dir. Richard Linklater)

Richard Linklater likes to take his time; Boyhood was shot from 2001 to 2013, following one boy through childhood, high school, and university. It’s a must-watch, for the moving experience of seeing a character grow up physically as well as emotionally, the technical achievement – the main cast stuck with it through the lengthy period, with Ellar Coltrane impressing more and more as he matures – and the unusual structure.

Characters dip in and out, beginnings and ends of relationships are missing, we never know how some scenes end. This is not how we’re told to make a film, and yet it’s brilliant, boldly fragmentary, a coming-of-age told in vignettes. It’s about how life is aimless, everyone’s just winging it. Who knows where we’ll be this time next year, or in twelve years time? It probably won’t be a logical extension of where we are now.

-Kieron Moore (KM)

The Duke of Burgundy (Dir. Peter Strickland)

Cynthia, an elegant butterfly professor, appears to employ Evelyn as her house maid. As increasingly sadistic scenarios repeat themselves, we discover they are sexual – and while Evelyn may seem like the slave, she is in fact the orchestrator and insatiable consumer of Cynthia’s deviant acts. Everything is charged with erotic possibility in Peter Strickland’s surreal, intoxicating world of soft, feminine sensuality that also happens to be a story of a masochist’s insatiable lust.

-GG

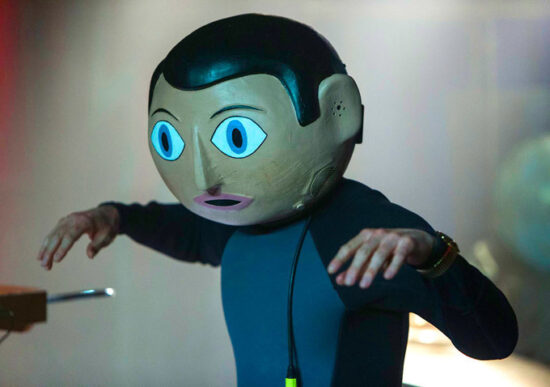

Frank (Dir. Lenny Abrahamson)

One of the best portrayals of mental illness ever put on screen. Surrounded by Stephen Rennicks’ beautiful odd pop songs, amazing performances – not least a mostly unseen Michael Fassbender and a brilliantly funny and moving script, this tribute to the outsider art of Frank Sidebottom, and outsider artists all over, is one of the most vital indie movies of the decade. In message and form it is a call to arms for the making of art as of value unto itself. A clarion call for tolerance and the embracing of individual difference in the sham face of the neo-liberal cult of the individual. All hail the Soronprfbs!

-NF

The Homesman (Dir. Tommy Lee Jones)

Travelling from west to east, the protagonists in Tommy Lee Jones’s second film for the big screen take the opposite direction than the heroes of the classic Western. Another difference from genre conventions is the fact that despite the title, women are at the centre of the action. The Homesman is beautifully shot, presenting landscapes which look like paintings. However, there is nothing peaceful in the story. The wide-open spaces of frontier America do not offer hope and optimism but are expressions of solitude and isolation. The journey of three mentally ill women through a hostile natural environment is filled with unsettling moments which are nightmarish, not only in the nocturnal scenes. The Homesman not only underlines that America has lost its innocence long ago, but in addition constantly challenges the very idea of normalcy.

-AG

Inherent Vice (Dir. Paul Thomas Anderson)

I can see this being my second, if not first or equal first, most controversial pick. But, I will die on this hill. This hill being the Inherent Vice is a masterpiece hill. It’s a mood. It’s a feeling. It’s hanging out and spending time for the pleasure of company and tagging along. The journey is the point, the time is the point, the plot points are not the point. Focusing on logic here is to miss the joys – the sounds, the textures, the gestures, the moments, as Doc Sportello (Joaquin Phoenix) tries to work out how he feels about his former love, Shasta Fay, and get a sense of the immediate world he lives in. It’s slow poetry that people thought was fast pulp. To me it’s perfect.

-NF

It Follows (Dir. David Robert Mitchell)

Anchored in teen horror conventions and yet startlingly original, David Robert Mitchell’s It Follows has a simple but winning concept – a supernatural stalker who you can pass on to another poor soul by having sex with them. The STI subtext is there if you want to read into it, but never played up or over-politicised; this is a horror film, and it knows it.

Maika Monroe’s Jay is an intelligent, active lead – vulnerable but not pathetic, attractive but not objectified – while Mike Gioulakis’ camerawork is stylish, but not for the sake of style; as it lingers on the landscapes of suburbia, it trains us to look out for anything unusual, all setting up a final shot that, though entirely ordinary if stripped of context, sends one hell of a shiver down the spine. Like all the best horror movies, It Follows makes the ordinary terrifying.

-KM

Love is Strange (Dir. Ira Sachs)

As the typical boy-girl rom-com gradually disappeared from cinemas in the aughts, two other types of relationship movie emerged in its place: the same-sex love story and the ageing romantic drama. Love is Strange is both, a delicate two-hander that examines the partnership between long-term lovers Alfred Molina and John Lithgow, as they face retirement in a New York they’re being priced out of just as it seemed the world was finally coming to accept them. Gently comedic even as it addresses heavier themes like modern bigotry and the tragic unpredictability of death, Love is Strange is a relationship film entirely free of cynicism. Could there be anything more reassuringly romantic than a story of two people still finding joy in each other after four decades?

-BM

Serial (Bad) Weddings (Dir. Philippe de Chauveron)

This French comedy uses clichés about otherness and racism and plays with them in an intelligent and amusing manner. It targets the bourgeois, Catholic and well-situated citizen who never thinks of himself as a racist, revealing intolerance and discrimination in sometimes coarse and sometimes subtle humour. The dialogue is swift and hilarious, and the situational humour well-paced. It is a film which allows the viewer to confront himself/herself and his/her own attitude towards the topics the film addresses. It also shows how humour can deal effectively with deeply rooted social problems.

-AG

What We Do in the Shadows (Dirs. Jemaine Clement & Taika Waititi)

Taika Waititi is one of the breakout filmmakers of this decade, making us laugh-cry with Hunt for the Wilderpeople before hitting it big with Thor: Ragnarok, one of the few Marvel blockbusters to flaunt a distinct authorial style. But before that, he and Jemaine Clement treated us to vampire mockumentary What We Do In The Shadows.

Following a house-sharing group of vamps through their everyday lives, there’s not a great amount of plot, but that hardly matters, because it’s one of the funniest films of the decade; one of those comedies that stays just as funny through multiple rewatches. Epitomised by Waititi’s character putting newspaper on the floor to avoid staining it with his victim’s blood, Shadows has an intense understanding of horror conventions and social norms and is relentless in its parody of both. The spin-off TV series is also well worth your time.

-KM

Whiplash (Dir. Damien Chazelle)

Damien Chazelle’s early life as an aspiring musician has influenced every film he’s yet made. His first and third were explicitly musicals, while his fourth was a proto-space opera that danced to an inextricable Justin Hurwitz score. Chazelle’s second and best feature, however, is rather a musical done like a thriller – a vaguely autobiographical telling of the filmmaker’s jazz drummer education as if directed by Brian De Palma. With Miles Teller as his proxy, Chazelle documents the exhausting, isolating effects of single-minded obsession for a young man who’d rather be remembered as great than good. First establishing the perfectionism of both Teller’s Neimann and J.K. Simmons’ drill instructor-like music teacher, Fletcher, Chazelle shoots musical performances like action setpieces, the tension rising as we wait for anyone under the bulldozing Fletcher’s tutelage to play a false note.

-BM