Beronica Garcia

Da 5 Bloods (Dir. Spike Lee)

Spike Lee’s Da 5 Bloods comes at a pivotal time for the Black Lives Matter movement; exploring the all-too-familiar stigmas of biasness, racism and PTSD through the lens of Black Vietnam veterans. Four wartime buddies reunite in Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) for two missions: find the gold they left behind & locate the body of the 5th “Blood” member, Stormin’ Norman (played by the late Chadwick Boseman). What starts off as a fun-loving excursion turns into a waking nightmare as they revisit past traumas and wounds they believed healed. The trip only displays the Bloods’ conflicting feelings of their wartime experiences, which has created for them race-related stressors. This is depicted by Blood brother, Paul (Delroy Lindo), who delivers a powerful soliloquy through the jungle, displaying the demons that continue to chase him after the war. A Spike Lee film is in and of itself an art to contemplate and treasure. He unapologetically addresses hot button issues that affect the African American community and get overlooked in the media. The poetic voice of Marvin Gaye begs viewers, at the end, to stop and ask themselves: “what’s going on” with the world around them?

Relic (Dir. Natalie Erika James)

Japanese-Australian writer and director, Natalie Erika James, debuted her feature-length film this summer, Relic. Kay (Emily Mortimer) and her daughter Sam (Bella Heathcote) go to look for grandma Edna (Robyn Nevin) who has disappeared. After going back to her childhood home, unsettling things begin to occur for Kay. Strange noises can be heard, and an ink-like substance spreads onto the walls and skin. The unknowable entity lurking in the house has seeped into grandma and has manifested into a maze from which there is no escape. An unexpected transition occurs at the end when mother and daughter realize the horror is not a ghoul but a mental disease that vines its way from generation to generation. The pressures of Alzheimer’s, which are known to be disorienting to the person and are demonized by others, are addressed in this film very vividly. This female-dominated cast exposes the realistic terrors of a degenerative illness which turns people into strangers to themselves and to their family.

Sound of Metal (Dir. Darius Marder)

Up-and-coming heavy metal drummer, Ruben (Riz Ahmed), and frontline singer girlfriend, Lou (Olivia Cooke), have come to a crossroads in the emotional drama, Sound of Metal, by director Darius Marder. Believing they have the perfect life together, things come crashing as Ruben begins to lose his hearing. Fearful he will turn back to a life of narcotics to cope, Ruben checks into a drug rehabilitation center for the Deaf, and Lou, in the meantime, flies back to her father in France. Although he puts up barriers to the kindness and hospitality of the Deaf community, bonds unexpectedly begin to form. Marder puts viewers in Ruben’s shoes, feeling his discomfort of muffled sounds and the isolation from the outside world. We follow in his journey of learning ASL within an eclectic group of people. Despite the fact that the story ends with Ruben losing two deep loves that have brought him stability over the years, he gains clarity on finally pausing to see the beauty of life.

Ada Pirvu

Druk (Another Round) (Dir. Thomas Vinterberg)

Four male friends, all high school teachers, are embarking on exploring the obscure scientific theory that a steady blood alcohol level can enhance human performance. But there is a profound character study that hides behind this equally appalling and comedic premise. Martin, played by Mads Mikkelsen, is the history teacher, one of the four friends and the one mostly stricken by a mid-life crisis. He appears as someone often lost within himself, simply not present in his own life anymore, and who – in a surprising emotional moment, while celebrating one of his friend’s 40th anniversary – finally admits he doesn’t know how he has ended up like that. Thomas Vinterberg’s film does neither judges its characters, nor justifies their actions or portrays them as interested in reclaiming lost youth. It humanely, openly, earnestly portrays them as they are in this point in their lives’ journey, showing resilience in times of hardship, comedic relief in moments of darkness. A beautiful, life-affirming dark comedy. And one more thing: you realise how good this film is just by thinking what an American remake would look like. Something that would come very close to Ruben Östlund‘s Force Majeure and the American remake Downhill – the American version will probably be one more obviously comedic, with appeal to the larger public, painfully losing the subtlety of an incisive portrayal of the modern human condition. Not only is Another Round one of the best films of the year, but it has the best ending, too. The film only gets better with that bittersweet closing.

Lovers Rock (Dir. Steve McQueen)

Steve McQueen’s Mangrove and Lovers Rock are both among my favourite films of the year. It was not the socially relevant theme that impressed the most about Mangrove, but the vivid storytelling, the cultural background of the black community that powerfully and beautifully comes to light (through colour, light, texture and music), the intensity of the actors’ performances. But what I appreciated about Lovers Rock even more is that this is the kind of film that makes you appreciate the medium of film more, rather than the story or the content. These days, cinema seems to lack experimenting with elements that are only specific to film, like McQueen does here. People tend to get caught up in telling a good story. From film I want more visuals, too. Lovers Rock is centered on a house party in 1980s London, people setting up the place, getting ready, kindling relationships. The black community is again at the forefront, just as in Mangrove (and all McQueen’s Small Axe films), but the framing of the story and style of filming are different here. Dance and music and the unique, innermost, electrifying emotions that result from that can only be experienced when lived, and Steve McQueen’s intimate filming approach gets you very close to that.

The Nest (Dir. Sean Durkin)

In Sean Durkin’s The Nest, Jude Law is Rory, an investment banker who moves back to his native England from New York with his American wife, Allison (Carrie Coon), and their two children. He is a good salesman, even great at using his looks and charm to sell things, but unfortunately what he is trying to sell the most is a fantasy. The family is starting to crumble in the chilly and majestic English countryside. The dark atmosphere creeping in makes you pay attention to things beneath the surface. That surface is something that Rory cares about. Greed is gradually creeping in, too. Allison comes from a hardscrabble background and although she had already been rather suspicious of their good suburban life, and despite her having something of Rory’s materialistic tendencies, her discomfort grows deeper with their move into a dramatic English mansion. What ensues is a wrenching psychological and haunting marital drama that is as cinematically powerful and beautifully tailored as it is bitingly poignant for these times. What remains if people let go of their illusions, or delusions?

Gabriel Solomons

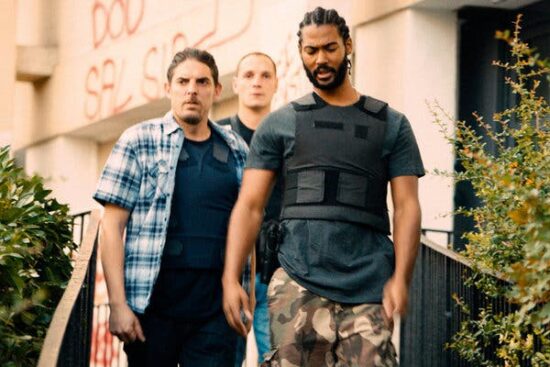

Les Miserables (Dir. Ladj Li)

Ladj Li’s Les Miserables is one of those rare cinematic marvels that – from the first moment – grabs you by the scruff of the neck and drags you, willingly, through a hotbed of racial tension and social discontent ala 1995’s La Haine.

The narrative is fuelled by Victor Hugo’s quote from the other Les Mis: “There are no bad plants or bad men; there are only bad cultivators” as groups of suburban youth are ensnared within a patriarchal structure of greed, corruption, fear and manipulation – destined to follow in the footsteps of elders whose selfish ambitions rely on blind obedience and allegiance.

The barely contained order of this district in the eastern suburbs of Paris (Montfermeil – where Victor Hugo wrote his famous novel) is threatened as tensions between the police, rival gangs and community ‘leaders’ are ratcheted up by an act of impulsive folly by one of the local lads – and which will be the touch-paper that ignites a rebellion by those impressionables who have been waiting for their moment to rise up.

The Lighthouse (Dir. Robert Eggers)

The Lighthouse is a beautifully unsettling tableau of epically batshit-crazy proportions. Willem Dafoe’s Crusty old boss man and Robert Pattinson’s tightly coiled apprentice lose themselves to the blackness of isolation and the lure of boozy delirium while tending to the titular lighthouse off the coast of Maine, as the weather worsens and the rations run low.

As madness quickly takes hold of these ‘keepers of the light’, confessions and dark secrets trigger a series of unfortunate events that uproot reality’s bearings, casting these tortured souls adrift in a swirling sea of mythic metaphor and folkloric symbolism.

Unlike anything I’ve seen for some time – this is essential cinema that will challenge your mind and invade your dreams.

Uncut Gems (Dirs. The Safdie Brothers)

The Safdie brothers managed to bottle lightning and inject an adrenaline shot of movie mayhem into the mainstream with this raucous examination of a chaotic life in free-fall.

The film’s frenetic pace, that thrums along to a prismatic Oneohtrix Point Never score, perfectly matches the emotional turmoil of Adam Sandler’s jittery jeweller in a relentless pursuit of the ultimate gambling win.