LA at dawn. Silhouettes of high-rises, bungalows and lines of palm trees merge together into a glowing mist. The urban jungle created through light and shadow, and new dreams that are always rising up, and old dreams that have turned to concrete. That’s the opening image from Michael Doster’s book Doster 80s/90s. And, for some reason, I associated it with the film Against All Odds once I had watched it.

Taylor Hackford’s 1984 neo-noir had as inspiration one of the greatest films noir of all time, Out of the Past (1947), “a film so dark and fatalistic that even the scenes in sunny California and heatstroken Acapulco look like overexposed nightmares”, wrote the Süddeutsche Zeitung. Robert Mitchum and Kirk Douglas had a climactic rapport every time they were on screen. Douglas’s character, a gangster by the name of Whit Sterling, hired Mitchum’s Jeff Bailey to find his runaway lover and bring her home at any cost. Jane Greer was the girl. Even before meeting her, her image had already, inexplicably, been set up for Bailey, part of his past and present. Kathie Moffat had the appeal and darkness, the beauty and brutality of the authentic femme fatale. Few others, if any, have achieved this. No foolish flirtations, no sentimentality, a chilling composure. She just went after what she wanted, remaining unperturbed as she tells Mitchum: “You’re no good for anybody else. You’re no good and neither am I.”

We meet Jane Greer again in Against All Odds. This time, she is Mrs. Wyler, the mother of the missing girl, Jessie (Rachel Ward). Mrs. Wyler is into real estate and has a plan of destroying a canyon and building houses for the rich. The boyfriend, the bad guy (James Woods as Jake Wise), is a gambler who hires a football player (for a team owned by the same Mrs. Wyler), Terry Brogan (Jeff Bridges), who has just been let go because of a shoulder injury, to track her down her and bring her back to him.

But Against All Odds cannot simply be written off as a remake, because it is clearly aware of the film it pays homage to and is firmly grounded in the times and style of the ‘80s. And it has that something that makes ‘80s movies special: it was made because that’s where the director’s interest lay, because that’s the kind of film he wanted to make, according to his interview with Bobbie Wygant, disregarding his previous films’ recipes for success, the studios’ expectations and what the audiences thought. Brogan does find Jessie – in Mexico, just as Mitchum had found Jane Greer in that Mexican café, all dressed in white, fooling him into appearing to be his dream come to life, not the messenger of his downfall that she really was – and the love triangle, the cause of all tension and suspicion and foul betrayal, ensues. Because Jessie Wyler is no dream come true for Terry Brogan either. And that’s good, because much of the film’s attraction lies in her scheming character. The most interesting movie characters are never black or white, are they?

In the same interview with Bobbie Wygant, Taylor Hackford said that Rachel Ward was the actress he wanted to work with on this film from the very beginning. “Had I done the film in the ‘40s, there would have been maybe 10 actresses that I could have chosen from,” he said. “There are not a lot of actresses today that would fit that bill. I wasn’t interested in just beauty, but intelligence and presence and substance.” But it was only when they met in person that he sensed there was something in her that he hadn’t seen on screen from her before, and that was exciting for him; he wanted to put that out there. And the Jessie Wyler character has that kind of a mystery, you can’t quite figure her out, none of the other characters can, least of whom Terry Brogan.

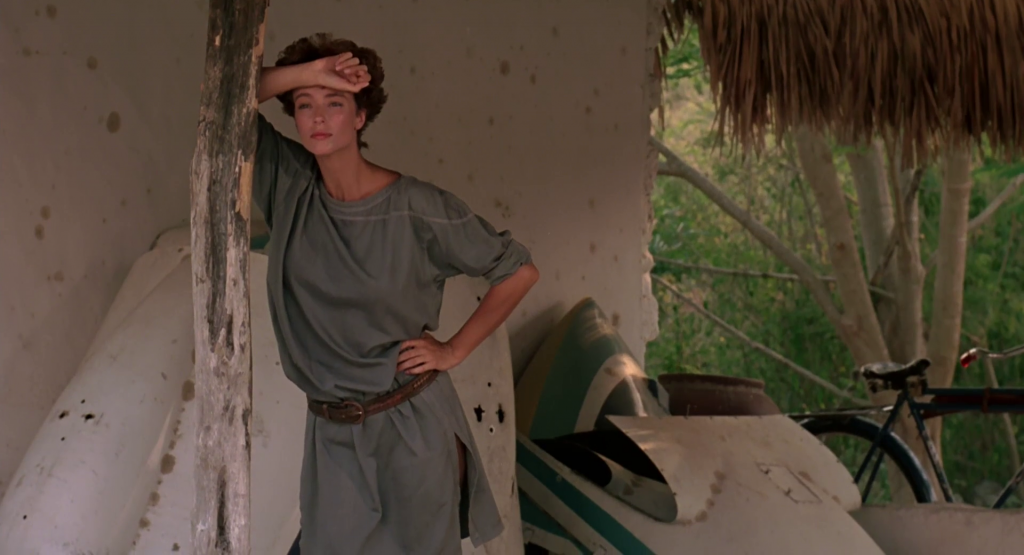

Jessie Wyler’s light clothes are the perfect disguise. Carefree, airy and sensuous, they are the perfect island-like life attire. The essence of unabridged style, white and khaki dresses (instead of the loud colours that were quintessential for the 1980s) in the most beautiful linens and crepes, extremely sensuous in their simplicity, carrying something from the Calvin Klein aesthetic and essence, that of reducing an item “until it is finally at its essence,” as Zack Carr, the creative director at Calvin Klein for three decades, told Donna Karan during one of her first days working at CK. Rachel Ward is sensuous and sexy wearing them, and so should a good noir femme fatale be. Her passionate appeal is so obvious that Brogan’s falling for her and downfall are inevitable. Because her white clothes from Mexico, starting with the white blouse she is wearing when Terry first sees her, represent the most insistent anachronism in the iconography of the femme fatale, another Out of the Past Mexico café moment, another perfect example of inverse symbolism.

And then Jessie Wyler is back in LA and the eighties style is felt more profoundly. The jacket with strong shoulders over a graphic t-shirt and loose-fit trousers – they could be jeans – turned up at the hem. Again I thought of Doster’s ‘80s fashion photography. “Allure. The look of the eighties needed that, to wear those clothes,” Doster said. “Fashion was fun in the eighties. There was no marketing pressure. People enjoyed life.”

There is not enough praise that can be sung to the broad-shoulder blazer and to how it encapsulated the entire feel of the eighties and ‘80s fashion: attitude. The “coat hanger” look that was invented by Hollywood costume designer Adrian, a silhouette that has intermittently returned to fashion, but never as feverishly as in the 1980s. Michael Kaplan, the costume designer for the film, was also responsible for the costumes in Blade Runner (in collaboration with Charles Knode), where Sean Young’s sharp costumes, a mashup of retro and futurism, were largely influenced by the tailored suits that Adrian designed in the late 1930s and early 1940s.

“How can dressing be simplified so that I can get on with my own life?”, Jessie seems to say as she defies her mother, playing dress-down in the garment symbol of power dressing at her mother’s formal party. A form of rebellion against her mother, but also underlining the femme fatale’s duplicity. Towards the end of the film, when the twists of the plot are finally untied and there is that last confrontation between Brogan and the villains, Jessie appears standing among the latter. The line between characters and her conflicting sides becomes even more blurry.

What are we to make of her final outfit, a green polka-dot dress under the glistening LA sun? That’s probably the most intriguing use of detail that questions her characterization. Brogan’s look in the eye is certainly telling us, and maybe trying to tell himself, too, that he hasn’t even grasped the complexity of the one he is looking at.

This piece is published courtesy of classiq.me