In the age of commercial chains and franchise operations, most hotels are anonymous environments that would seem to offer little in the way of inspiration for filmmakers looking for an appropriate location to stage an exercise in unease.

The Bates Motel in Alfred Hitchock’s Psycho (1960), the Overlook Hotel in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980), the Pine-Wood Motel in Nimród Antal’s Vacancy (2007) and the Dolphin Hotel in Mikael Håfström’s 1408 (2007) are all examples of the unexpected perils that lie beyond the cinematic check-in desk, while David Lynch, arguably the master of subverting the most seemingly ordinary of settings, served as executive producer of the strange television series Hotel Room (1993), although it was abruptly cancelled after a mere three episodes. As hotels are supposed to accommodate the needs of their guests and offer comfort and relaxation, directors have taken macabre delight in twisting their intended purpose and turning them into traps for physical and psychological torment from which central protagonists may be unable to check-out.

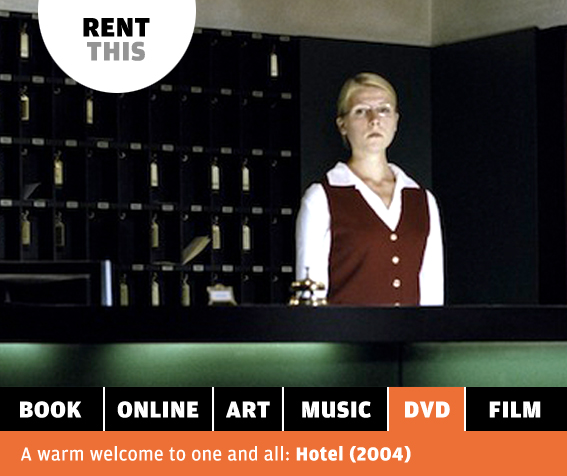

Jessica Hausner’s Hotel is an eerily atmospheric addition to the sub-genre which toys with the audience’s awareness of filmic trickery from its opening frames; the lush music score that accompanies the credits turns into elevator muzak as Hausner switches to the lift of the Hotel Waldhaus, only for the muzak to cut out completely due to a fault with the speakers. The two people in the elevator are Mr. Kross (Peter Strauß), the manager of the establishment, and Irene (Franziska Weisz), his new employee. Irene smiles sweetly, pretending not to notice the problem with the speaker, an early example of the politely accepting attitude that she will not dispense with until it is too late. The hotel is located deep in the woods of the Austrian Alps and Irene discovers that the girl she is replacing has vanished without a trace, although none of the staff seem particularly concerned about what may have happened to her predecessor. Due to her professional manner, Irene finds herself being assigned more responsibilities, but although she informs her parents via phone that ‘everything is fine’ and that her co-workers are ‘really nice’, it soon becomes apparent that she may not be a welcome addition to the team; her necklace is stolen while using the hotel swimming pool, the management give instructions but rarely make proper conversation, and refusing a favour to a co-worker leads to a burgeoning rivalry.

Hotel may be light on plot, but it is superbly shot and structured. Hausner methodically establishes Irene’s routine – daily duties, evening swimming, cigarette breaks, dancing at the local night club – before inserting unsettling strangeness; locked doors, sudden violence during a night out, techno-fuelled parties in the common room, the return of Irene’s necklace with the vague explanation that it was ‘found in the woods’, and the aforementioned elevator muzak unexpectedly crackling through the speakers once more whilst Irene is working the late shift. Characters keep disappearing into the darkness of hotel corridors, the surrounding woodlands or nearby caves; Hauser’s camera eventually follows Irene into the void in pursuit of answers, although the rather sudden but tonally appropriate ending only leads to further questions. Recurring shots of the dimly lit hotel pool and the faded purple curtains in Irene’s room suggest sinister secrets, while Weisz’s finely balanced performance treads the delicate balance between growing curiosity and the acute awareness that digging too deep may not be in her best interests.

When it toured the festival circuit from 2004 to 2006, Hotel courted favourable comparisons with such similarly cryptic genre-benders as Mulholland Dr. (2001) and Hidden (2005) but the fact that it has only received a belated UK release following the art-house success of Hausner’s subsequent feature Lourdes (2009) serves to show that such films are not considered marketable unless the name of an established auteur like David Lynch or Michael Haneke is attached. Although many of the tropes of the horror genre are employed throughout the slender running time, Hotel adopts an existential approach to cinematic terror, unnerving the audience by tackling such issues as emptiness, loneliness and the loss of identity. It is suggested that Irene is gradually adopting the identity of the missing girl when she starts wearing the red-rimmed glasses that she finds in her room – a possible reference to Twin Peaks (1990-1991) – and that her fate is sealed before she plans her ‘escape’, enabling Hausner to build suspense through slow pacing, the stilted interactions between Irene and the other members of staff and consistently creepy sound design which recalls Eraserhead (1976).

Although some of the disgruntled guests and conference parties that arrive at the Hotel Waldhaus provide moments of deadpan humour, Hotel is mostly the kind of minimalist mood piece that lingers in the memory and may prompt discerning viewers to make a return visit.

John Berra