At the end of the 19th Century, the Lumiere brothers’ short film Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat (1895) defined the technological advancements of the era, and terrified audiences who, having seen nothing like it before, believed the train would fly out of the screen. Over a hundred years later, at the turn of the 21st Century, the arrival of a train in Lee Chang-dong’s Peppermint Candy (2000) is used to signify so much more than wonder and awe, being a key part of his storytelling process. This shows not just how far cinema has travelled, but also that true auteurs do not forget its humble beginnings.

Peppermint Candy is that rarest of films, a devastatingly real human drama relayed in an innovative form of storytelling that is both masterful and timeless in its execution. As a train passes through a pitch black tunnel into the ever growing burst of daylight at the end, so begins our journey with Kim Yongho (Sol Kyung-gu); a middle aged Korean whose life has passed him by almost as fast as the speeding carriages that traverse the screen. Told in reverse chronological order, Peppermint Candy begins in the Spring of 1999, just moments before Yongho makes a final decision to take his own life on the train tracks situated where he met his first love, and works its way back over the course of 20 years to unravel the reasons that have led this desperate man to suicide.

Used as a framing device between time shifts, the train shots were filmed from the back of a moving carriage and then reversed in order to emphasise the journey backwards through the defining moments of Yongho’s life. Chang-Dong’s choice to painstakingly sift through hours of footage to pick the most evocative and beautiful shots certainly shows; falling blossom from a tree rises back to the branches it once left, a passing jogger appears to run backwards in slow motion, and a family appear to linger cautiously watching the train pass by. These natural scenes indicate Yongho may finally be at peace with himself but the audience are still invited to take a trip back into Korea’s troubled past to see how seemingly insignificant actions can lead to consequences capable of driving a man to despair.

In a strange turn of events, moments from certain points in Yongho’s life mirror those which come later on, or vice versa, signifying the repercussions of simple acts and ironic twists of fate that cannot be avoided in everyone’s passage through life. We see the reasons why Yongho’s marriage and working life fail, and ultimately the destructive act which leads to the loss of his innocence and plagues his existence until the very end.

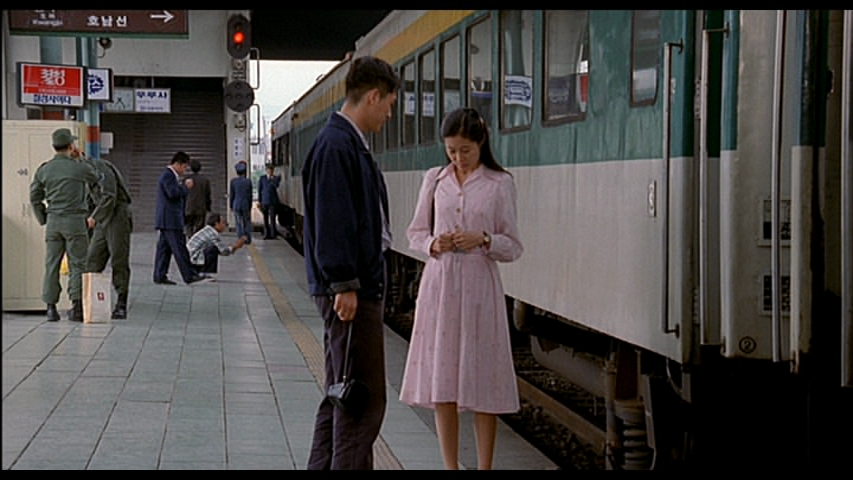

Many classic love stories involve train journeys, with romances blossoming from chance encounters or a last minute decision to catch a different train, but unlike the hopefulness of these meetings in films such as Before Sunrise (Richard Linklater, 1995) and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (Michel Gondry, 2004), the appearance of trains in Peppermint Candy reflect moments of weakness in Yongho’s life. At various points throughout the film our protagonist is seen betraying his wife, destroying a gift from his first love and standing by whilst his friends tackle an assailant, all of which are accompanied by the passing of a train in the background, which acts as a constant reminder of Yongho’s inevitable fate.

Akin to Gaspar Noe’s Irreversible (2002), which used a similar narrative twist as a plot device, Peppermint Candy’s closing scenes are moments of serene beauty as Yongho experiences a fleeting glimpse of young love. This seemingly peaceful end to the film is marred by the bittersweet knowledge of events to come; just as Yongho regrets the paths which he chose as a young adult, a mature audience will certainly relate to the loss of innocence and sense of regret that befalls not just our protagonist but everyone as time passes by.

By encapsulating certain periods in recent South Korean history, Chang-dong ensured that his film would resonate with a domestic audience and although some of his references may be lost on international audiences this is unlikely to detract from the overall experience. It is no surprise that such an articulate and politically aware director went on to become South Korea’s minister of Culture and Tourism back in 2003, but it was also a relief when he returned to film-making as he continues to deliver both beautiful and powerful dramas, even if his later outings do not reach the near perfection of his overlooked masterpiece.

As the Lumiere brothers were shooting footage of a train’s arrival back in 1896 they would have had no idea just how immersive and powerful the medium of film would continue to be in the next two centuries and beyond.