Nat Faxon and Jim Rash’s The Way, Way Back is a typical teen movie in so many ways. It captures that feeling of taking a holiday from teenage angst – a holiday with the promise of being whoever you want to be for a short period of time.

In a way, however, the film feels almost too perfect, and it is in this sense of perfection the film cultivates that we come to understand the main character, fourteen-year-old Duncan, and how badly he must need this version of the summer to give him strength to go back to his normal life, to carry on. It’s almost as if what we are watching is Duncan retelling the events of his summer vacation to his peers at school, presenting his experience as he dreamed it could be and needed it to be – embellishments, exaggerations et al.

The film is certainly nostalgic but it also serves as a beautiful example of how teenagers nostalgically create narratives for their lives as a way of understanding and even surviving some of the most demanding years. It captures how teenagers curate a sense of self before they have cultivated one experientially.

Most of the adults are like children. Duncan’s Mum (Toni Collete) and her slimy boyfriend Trent (Steve Carell) smoke pot, get drunk, and giggle. They do these things with Trent’s similarly childish friends at the beach house where Trent has taken them for the summer. The person who will become Duncan’s hero, the mesmerising Owen (Sam Rockwell), is a man-child who runs the waterpark that Duncan stumbles upon during a cycled escape from the beach house one day. Owen’s male work buddies are similarly regressive.

They all represent aspects of Duncan’s teenage life that he can grasp and understand – his fear, his desire for freedom, his developing sexual appetite and the spectre of his primitivism – but little else, because he himself has experienced little else emotionally.

Owen is hero-worshipped by Duncan. He fulfills the roles of father, friend and cool older brother in one. He is confident, hilarious, independent, aloof, irreverent and sexual. He’s perfect. Just like the girl who Duncan meets is perfect.

Susanna is the daughter of Betty, Trent’s lewd and borderline alcoholic beach house neighbour. Susanna refrains from gossiping with Trent’s daughter Steph and other pals who she has clearly grown apart from since they saw each other the previous summer. She is confident in herself and she likes Duncan. She makes that clear constantly, though he is oblivious.

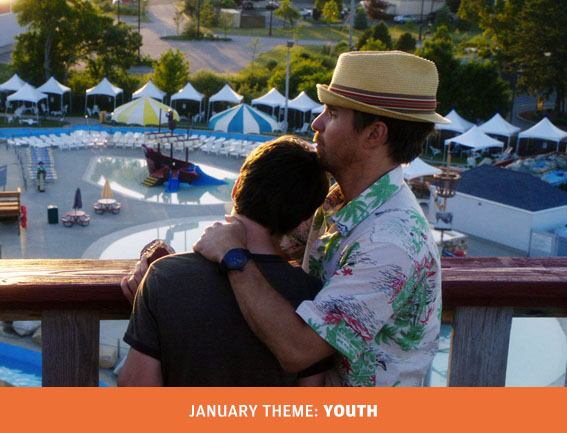

Duncan’s first day initiation when he lands a job at the water park similarly feels too good to be true. This awkward, gawky teen trundles over to a ‘dance-off’ having been instructed to take the exhibitionists’ cardboard away. He shuffles through a throng of buoyant, celebratory kids who are gleefully watching cool older teens bust their moves.

They don’t like Duncan stopping them in their tracks and demand that he must show them his moves before they will allow him to remove the cardboard as instructed. This moment, fraught with tension and potential disaster, should by rights descend into a humiliating debacle, but it doesn’t. That is impossible in Duncan’s narrative and this moment becomes one of triumph, community and inclusion despite his clear lack of confidence and ability.

We know it will work out for Duncan, because he’s telling us it did. Whether it really did or not, or to what extent it played out as he’s telling us, doesn’t matter and we’ll never know. Duncan gets it all because it’s his narrative. But he has to live with his version, including the fantasy elements. He will grow into a person who doesn’t need to create narratives for his own life to such an extent. Or maybe he won’t.