Whilst the ‘road movie’ most readily conjures up images of the ever changing social and physical landscape of America, from Easy Rider to Little Miss Sunshine, it is by no means limited to one nation’s collective experiences. All around the World, from Australia to Scandinavia and all places in between, the genre has attracted all manner of directors, whose work ranges from exploitation to art house, and all manner of narrative subjects. Here are a cross-section of road movies, drawn from all eras, which display unique visions of the emotional and physical journeys that define the genre.

Mad Max (Dir: George Miller, 1979)

With such a vast and varied landscape Australia is an ideal fit for the exploration of the road movie genre. The likes of The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (1994), Road Games (1981) and Walkabout (1971) have all used the terrain of the country as a backdrop for their own particular narratives and unique spins on the road movie. Miller’s dystopian vision also plays with the genre conventions that provide its framework. Filmed around Melbourne, Victoria – a combination of barren semi-desert plains and lush farming land – Mad Max made an international star of its lead, Mel Gibson, and spawned two sequels and countless post-apocalyptic action flicks.

The ‘journey’ taken by Max, a highway patrol officer, isn’t the usual road to emotional enlightenment or redemption seen in many of the genre’s offerings. Instead, it’s a high- octane revenge movie where the path taken is from civility to outright brutality. Miller combines the surrounding environment with the narrative to great effect; scenes of violence and chaos largely take place on the endless stretches of highway that crisscross the state and the more tranquil scenes occur in the familial home or the more welcoming farming region.

Whereas the open road is often seen in movies as the gateway to freedom, escape or adventure here it is a place of terror, lawlessness and death. The space where civilisation breaks down and anarchy rules the road becomes ‘mad’ Max’s new natural environment.

La Strada (The Road) (Dir: Federico Fellini, 1954)

Fellini’s La Strada is very much a classic ’emotional journey’ narrative, as itinerant strongman Zampano (Anthony Quinn, in a role he had coveted) and Fellini’s wife and frequent collaborator Guilietta Masina as the naïve, emotionally fragile Gelsomina impact on each others lives in bizarre fashion. Sold for 10,000 Lira by her poor mother to Zampano as a replacement assistant for her sister Rosa, whose death is never fully explained, Gelsomina is eager to please, and to learn from, her new master. As they travel from town to town performing their act (passing through rural, coastal and mountainous regions), Zampano’s inherent cruelty and volatile nature threatens to break the spirit of his childlike, borderline savant assistant.

Gelsomina’s surreal mixture of nonsensical behaviour and youthful innocence is the polar opposite of the older, bitter Zampano: his booze fueled machismo, womanising and brutal streak both fascinate and appall his young companion. With her spirit stretched to breaking by Zampano’s behaviour, Gelsomina is entranced by Il Matto (the fool), Richard Basehart’s tightrope-walking circus performer, who offers her an alternative path in life. Torn between her blind loyalty to Zampano and the possibility of freedom and genuine affection with Il Matto, Gelsomina is finally crushed when the long-standing fued between the two men ends with Il Matto’s tragic death at Zampano’s hands.

Love, loyalty, loss and grief dominate the emotional territory traveled by both Gelsomina and Zampano – with ignorance, regret, guilt and the stark reality of his actions and their terrible consequences ultimately leaving Zampano a broken man.

Kandahar (Dir: Mohsen Makhmalbaf, 2001)

Iranian director Makhmalbaf’s Kandahar, with scenes filmed secretly in Afghanistan, is part reportage / part human drama whose serious subject matter (loosely based on a real life incident) sets it apart from the majority of films dealing with physical and spiritual journeys. Afghani-born journalist Nafas (Nelofer Pazira), now a citizen of Canada, is smuggled across the Iranian / Afghani border in a bid to save her sisters life. (Having lost her legs to a landmine, she was left behind by her family when they fled the country years before.) Nafas has three days to reach Kandahar, from where her sister has written to her that she will take her own life during the last solar eclipse of the 20th century. The simple storyline allows Makhmalbaf to explore life under Taliban rule. Released prior to 9/11, it was after the attack on the twin towers that Kandahar suddenly became the most important political film of its generation.

Shot in verite documentary style the film is an alternately harrowing, tragic and surreal exposé of life under the rule of religious extremists. Traveling by helicopter, three-wheeled van, on foot and by horse and cart across the barren landscape, where the social and cultural conditions of the population are as harsh as the surrounding environment, Nafas encounters thieves, beggars, villagers, Taliban patrols, Red Cross doctors, a wedding party and, most unexpectedly, an African-American Muslim convert posing as a doctor. Those whose paths she crosses display a mixture of stoicism, cynicism and desperation. Kandahar is a unique viewing experience highlighting the effects of oppression on a nation’s psyche.

Week End (Dir: Jean-Luc Godard, 1967)

Marking the point at which Godard largely abandoned narrative cinema, Week End is a tour de force of surreal imagery, furious energy and savage satire. An uncompromising attack on the modern consumer society, political ideologies and cinema itself, Godard’s movie is by turns dystopian, comic and extreme. The sparse plot sees a bourgeois Parisian couple, Corinne (Mireille Darc) and Roland (Jean Yanne), take a trip into the French countryside to complete their criminal plans to secure a family inheritance. Godard uses this premise to launch them headlong into a cultural, philosophical and socio-political nightmare, as the road and the surrounding landscape becomes a battleground for the very heart of French society. Initially, the pair are caught in a seemingly unending traffic jam; crash victims, bickering couples, wandering livestock and children playing in the road mingle with the vehicles in Godard’s seminal 10 minute tracking shot.

As the couple head deeper into the countryside events become stranger and increasingly violent as a slew of bizarre characters cross their paths. With a landscape increasingly resembling a Ballardian scrap yard, littered with the wreckages and corpses of multiple pile -ups, the couple are exposed to robbery, rape, murder and cannibalism. When a passing motorist asks Roland ‘Are you in a film or reality?’ Godard demolishes the fourth wall. One of the many onscreen titles announces that Week End is ‘A film adrift in the Cosmos’. Defiantly avant garde and still as fresh as ever, this is required viewing for anyone seriously interested in the possibilities of the ‘cinema of ideas’.

El Topo (The Mole) (Dir: Alejandro Jodorowsky, 1970)

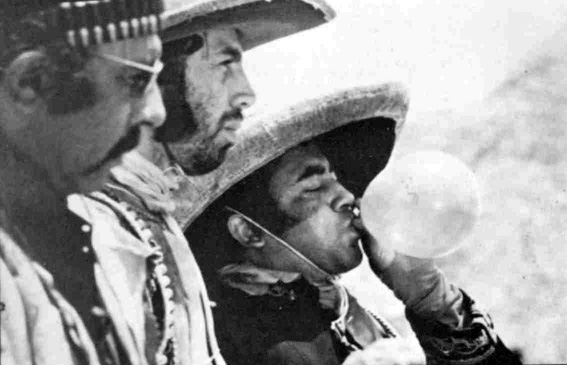

A cult favourite on the midnight movie circuit, Jodorowsky’s El Topo is both a road movie and a spaghetti western like no other. Championed by figures as varied as David Lynch, The Mighty Boosh, John Lennon and Marilyn Manson, El Topo takes the framework of a road movie and splices it into an allegorical Western dealing with mysticism, spirituality, enlightenment and existentialism. Striking imagery, graphic violence and copious nudity collide in the warped vision of its director / star. El Topo (Jodorowsky himself) is a tormented, black-clad gunfighter roaming the sun-bleached terrain of the Mexican badlands, sometimes robbing and killing to survive and, at other times, through a sense of injustice and religious fervour. The film is filled with Christian symbolism and peopled with an extreme collection of grotesques including insane bandits, mystical gunmen spouting Eastern philosophy, the physically deformed and a degenerate religious aristocracy. Challenged by his lover to duel with the ‘four masters of the gun’, El Topo completes his mission only for her to gun him down and leave him for dead.

Spiritually reborn as a monk-like figure, El Topo assumes the mantle of saviour to those who nursed him back to health: an ex-communicated and physically deformed clan, the outcome of continuous incest, who were banished from their home town. The excessively bloody climax, including the massacre of El Topo’s flock and his self-immolation, is in keeping with the rest of Jodorowsky’s hyperbolic tale. El Topo has had its own rebirth of late: after years of limited screenings and hard to find bootleg VHS copies it was finally released on DVD in 2005, and is now freely available for a whole new generation to discover.